‘Everybody in the Hispanic community knows someone who got it. They have seen what COVID does to people’

By mid-April, Yanet Garcia feared the worst.

She had heard about people in Culpeper County’s Hispanic community getting sick with what appeared to be COVID-19, and she realized it was likely to spread quickly.

She knew that many of Culpeper’s Hispanic families had multiple generations living together, and that they shopped in the same places, went to the same churches. More troubling was that so many Latinos worked together in nurseries or warehouses.

“The virus was going to feed itself,” said Garcia, a longtime Culpeper resident and an activist in its Hispanic community.

Garcia also was aware of what in the early days of the pandemic was COVID-19’s Catch 22: Because it was so difficult to get tested, people couldn’t prove to their employers that they had contracted the virus. So, she said, many went to work sick.

(Graphic/Laura Stanton)

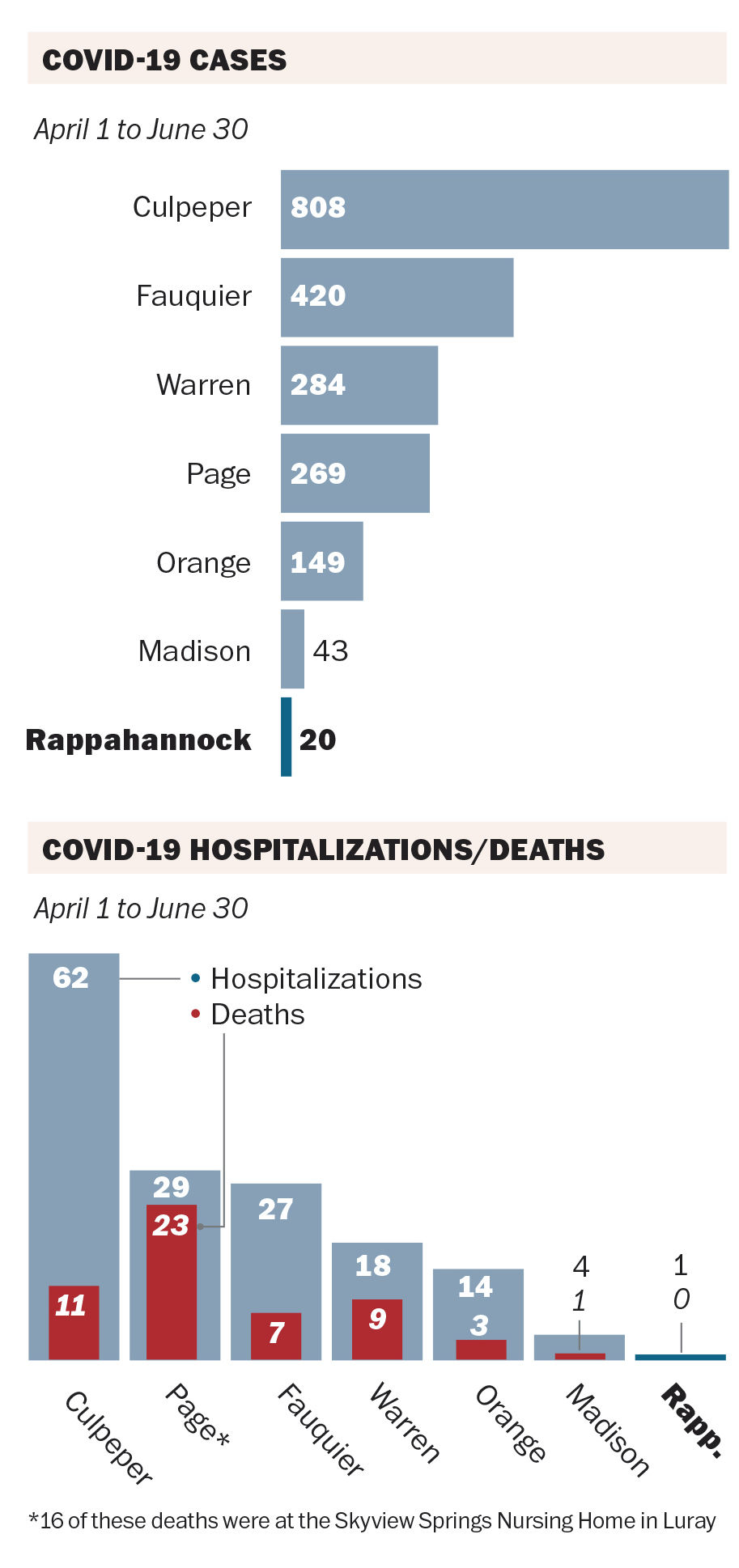

In the first week of April, only six cases of COVID-19 were reported in Culpeper. By the last week of that month, the weekly count was 10 times higher. By the third week of May, the total number of confirmed cases had spiked above 500.

Flattening curves

That number has climbed over 800. Sixty-three people have been hospitalized and 11 have died in the county. All are easily the highest totals in the region. Although the statistics are dramatically lower in Rappahannock — a total of 30 confirmed cases to date — many Latinos who work here live in Culpeper.

Yet Culpeper’s COVID chart has flattened in the past month. Some of that is due to herd immunity — those who have recovered can no longer pass the virus on. Some is the result of improved outreach and communication with the Hispanic community, especially when it comes to expanding testing options.

Another factor has been the contact tracing efforts of staff and contractors with the Rappahannock Rapidan Health District (RRHD), which covers Rappahannock, Culpeper, Fauquier, Madison and Orange counties. This involves methodical tracking of how the disease has spread in order to determine who needs to be quarantined.

Not that there haven’t been lessons learned, lessons that could be critical if the COVID virus surges again in the region in the coming months, as some public health experts fear.

“That decrease in cases has been a huge positive, but it brings with it a negative,” said Dr. Wade Kartchner, RRHD’s health director. “I think people will become more complacent. I hope not, but that’s the negative I see.”

Spotting an outbreak

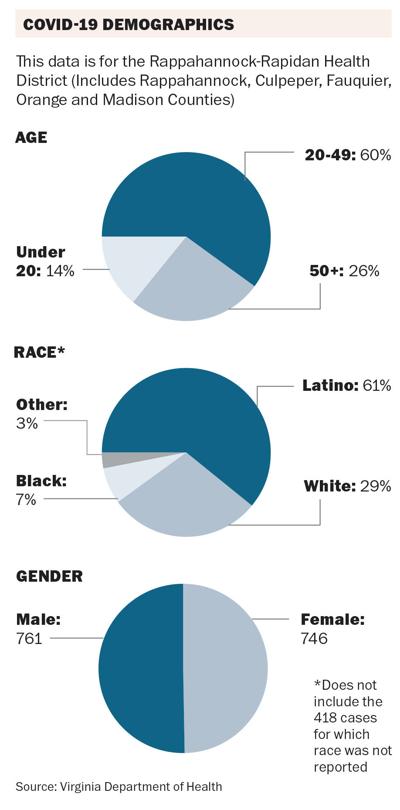

Once COVID reports began coming into the RRHD office, it soon became clear that the virus was particularly prevalent among Culpeper’s Hispanic families. (To date, 60 percent of the COVID cases — for which race was reported — in the entire health district have identified as Latino). In late March, Kartchner and April Achter, RRHD’s population health coordinator, participated in a virtual town hall meeting presented in both English and Spanish. A few weeks later, Kartchner took part in a Spanish-only program.

April Achter, population health coordinator for the Rappahannock/Rapidan Health District, participated in a virtual town hall meeting presented in both English and Spanish so all area residents understood the severity of COVID-19. (Photo/Luke Christopher)

But, Garcia suggested, that type of messaging was less likely to reach its intended audience than social media platforms popular in the local Hispanic community, such as a Facebook group page called Impactando Culpeper (Impacting Culpeper).

Also, some of the informational material from the RRHD initially was available only in English. And, as the virus spread and it was necessary to ratchet up contact tracing, few on the RRHD staff were bilingual. Staffers had to rely mainly on LanguageLine, a translation service. Eventually, the agency was able to hire some contractors who spoke Spanish.

Daniel Ferrell and April Achter are happy that Culpeper’s COVID chart has flattened in the past month, partly due to herd immunity. What the future holds in store is anybody’s guess and everybody’s worry. (Photo/Luke Christopher)

That made a difference, suggested Daniel Ferrell, the RRHD epidemiologist who oversaw the contact tracing process. “Initially, it took more reassuring to get people to answer our questions,” he said. “We had to let people know that we weren’t there to collect information on immigration status. But once we could start having real conversations, that helped bridge the gap.”

Disease detectives

(Graphic/Laura Stanton)

Tracking the spread of a disease as contagious as COVID-19 is a demanding and often tedious job. It involves working outward from confirmed cases and trying to find anyone who has been within six feet of them for more than 15 minutes, then contacting those people, telling them they need to be quarantined and determining where they’ve been, and with whom.

Ferrell explained that one confirmed case might mean tracking down another dozen people, and often, considering caller ID, that can require multiple calls to reach each one. At the peak of the outbreak in May, as many as 20 people at RRHD were spending most of their time trying to reach strangers to ask them a lot of personal questions.

“Contact tracing is difficult,” said Achter. “It’s time-consuming. It’s labor-intensive. It relies on people being willing to answer the phone. And then having them follow our recommendations.”

One advantage the contact tracers had was that they were able to focus on a relatively contained set of families and businesses — unlike the more random “community spread” outbreaks now occurring in parts of Florida, Texas, Arizona and California.

“It’s always easier to trace from A to B to C,” Ferrell said. “But once you have community spread, it gets more difficult to link one case with another case with another. At that point, you just assume it’s everywhere.”

Turning points

Garcia admits that she was initially frustrated by what she saw as a slow response by public officials to the outbreak in the Hispanic community. A key first step came when, after urging by Garcia and other activists, RRHD officials visited businesses where many Latinos were employed to both ensure that the companies were taking safety precautions and have workers reassured that they wouldn’t lose their jobs if they got sick.

Another turning point came in mid-May when the local activists, working with the RRHD and the Culpeper Medical Center, organized a free, drive-through COVID-19 testing event outside the University of Virginia Primary Care Commonwealth Medical Center. A total of 185 people were tested. Eighty were found to be positive.

During a two-week period between May 13 and May 26, 347 new COVID-19 cases were confirmed in Culpeper, and 22 people were hospitalized. Since then, the numbers have fallen steadily, dropping as low as only six new cases the last week of June.

Garcia thinks a big reason is that the Hispanic community now is much better educated about the disease and how to avoid it.

“Everybody in the Hispanic community knows someone who got it,” she said. “They have seen what COVID does to people.”

For health care professionals like Achter and Ferrell, the challenge is to keep motivated the people who haven’t had personal experience with the disease.

“It may seem like COVID’s not affecting you,” said Ferrell. “But you never know who you’re going to interact with on any given day, and you don’t know who that person is going to interact with. You might have a conversation with somebody who has a connection to someone who is at high risk.”

Achter made a similar point.

“Usually when we ask people to take on a certain behavior, it’s to protect themselves, like when we ask them to wear a seat belt,” she said. “But if we ask someone to wear a mask, that’s to protect the rest of the community.

“I understand that a mask can be uncomfortable. But even if you’re not elderly or immunosuppressed, I bet some of your friends are or someone in your family is.

“It’s really our role to take one for the team.”