With state budget in limbo, higher real estate, new cigarette taxes possible

County and state budget plans are unfolding on dual tracks: the Rappahannock County Board of Supervisors this week began digging into a proposed set of tax increases they hope to avoid, while state lawmakers have only general plans for resolving the budget impasse that’s causing the stress.

Noting that the parallel negotiations in Richmond and Rappahannock aren’t moving in lockstep, County Administrator Garrey Curry made a commitment to “maintain flexibility in the absence of a finalized state budget.” That means that in the likely event that the county adopts a budget before the state does, supervisors can undo any new taxes if the state eventually comes through with funding for the schools.

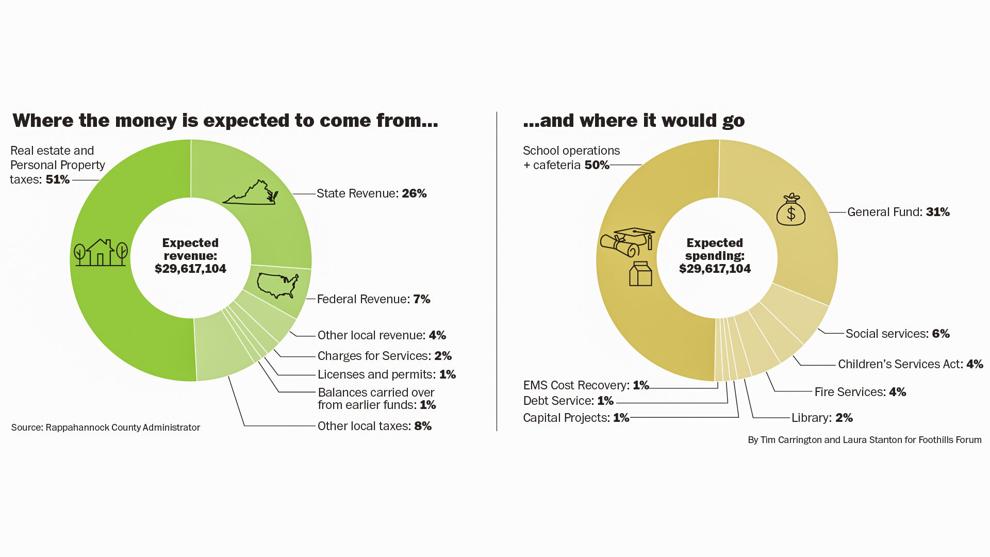

The proposed county budget of $29.6 million is a slight decline from the $32.7 million in the current fiscal year. The county plan must be adopted by mid-May, with the fiscal year beginning July 1; but the state process could drag into June.

In addition to reserving the flexibility to make major adjustments during the new fiscal year, the plan embodies five other priorities:

-

To maintain existing levels of service across all functions of government

-

To honor commitments to regional and partner agencies

-

To provide a 5% salary increase to county employees, consistent with the state’s compensation guidelines.

-

To enhance the level of local fire and rescue service

-

To meet the schools’ needs, independent of the state’s actions (this commitment links to the proposed tax increases, which would enable the county to infuse the schools with $547,163 to partly offset the shortfall from the state).

The most significant tax hike in the proposed budget would come from Rappahannock’s tax on real estate. The proposed budget would increase this levy to 57 cents per $100 of assessed property value, up from the current level of 55 cents. The change would generate $387,200 of additional revenue, bringing the total from real estate to $11,047,200, the largest contributor to the Rappahannock budget.

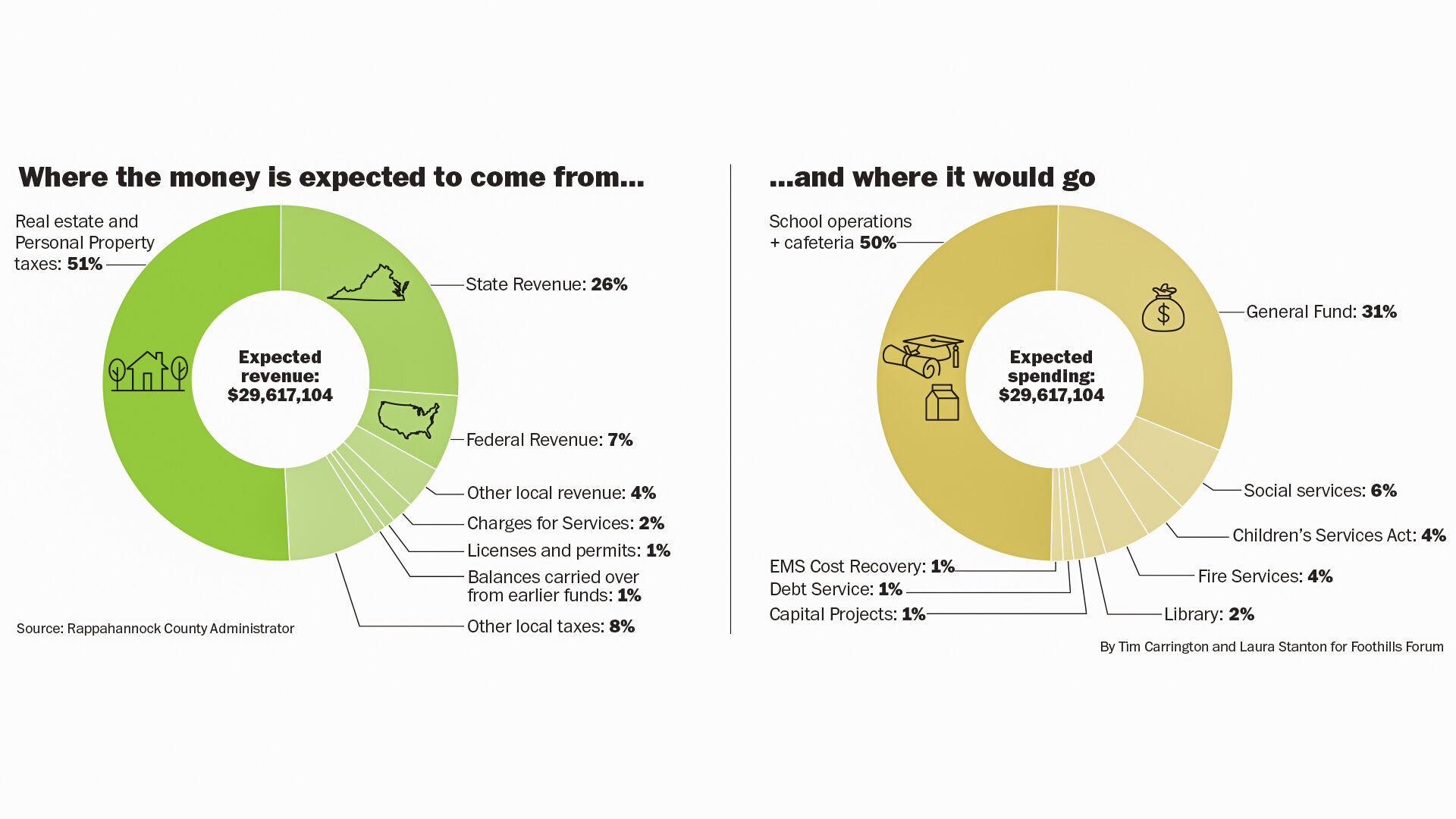

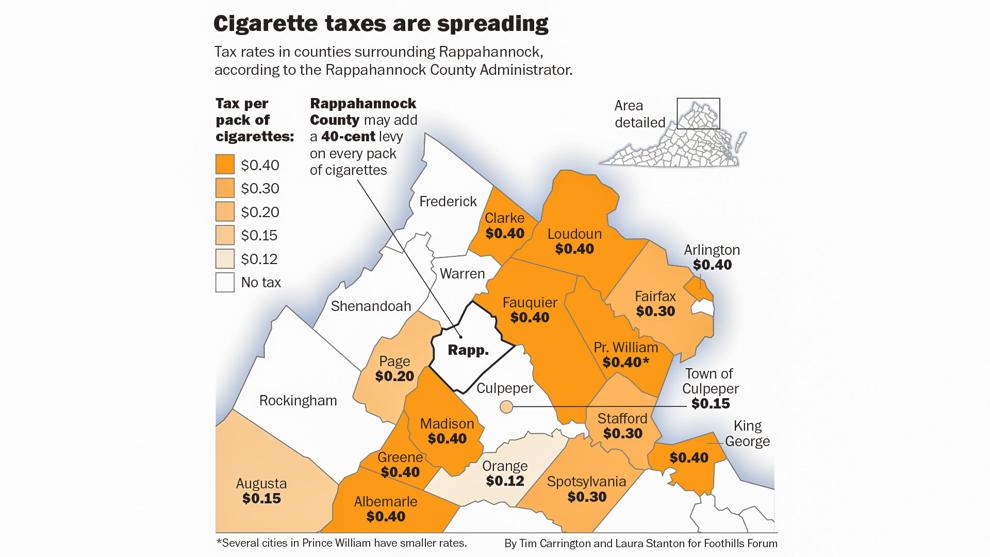

The county may tax smoke as well as land, through a 40 cents levy on every cigarette pack sold in Rappahannock. Piedmont Supervisor Christine Smith doesn’t smoke but nonetheless opposes the move, warning that the tax would send smokers over county lines to avoid the new tax.

(Graphic/Tim Carrington and Laura Stanton)

But cigarette taxes are spreading, and smokers may have to travel broadly to avoid them: Fauquier, Clarke, Loudoun, Arlington, King George, Madison, Greene, and Albemarle counties have the same 40 cent tax that Rappahannock is weighing. Fairfax, Stafford, and Spotsylvania counties tax cigarettes at 30 cents a pack, while Page County weighs in at 20 cents. Augusta County collects 15 cents a pack, and Orange County, 12 cents. Culpeper County doesn’t impose a county-wide tax, but the Town of Culpeper collects 15 cents a pack. To the north, Warren County emerges as the one contiguous county without a cigarette tax.

Smith also called for dropping a plan to fund a part-time recruitment and retention coordinator in the Sperryville Fire and Rescue Operation. The position would cost $41,424.

Jackson Supervisor Ron Frazier, who participated in the initial budget meeting through a digital connection, also opposed any cigarette tax, while noting that like Smith, he doesn’t smoke. “It’s just going to hurt local people,” he said, adding that the tax likely would fall short of generating the $37,000 budget planners are predicting for the six months it would be in effect in the next fiscal year.

As talk of finding new revenues continued, Smith suggested the supervisors consider doubling the lodging tax from 4% to 8%. Chair and Wakefield Supervisor Debbie Donehey returned to Smith’s argument that smokers would buy cigarettes from neighboring counties, reasoning that “if we become the most expensive, it’s easy to go spend the night over the mountain.”

Hampton Supervisor Keir Whitson held out the hope that the supervisors could find a way to avoid raising residents’ tax payments. “This doesn’t seem insurmountable,” he said, though he didn’t offer specific suggestions beyond combing through the school budgets more closely. A working session on Monday focused on details in the school budget, with a hope, as yet unfulfilled, of finding some easy spending cuts.

The state’s budget impasse, while hitting the school budget most deeply, also is throwing other budget items into uncertainty. A forest sustainability fund might receive $235,000 from the state, or be zeroed out. Funds for a currently unfunded position in the county treasurer’s office could come in at $13,600 or, nothing at all. State support for the Rappahannock County Public Library could be anywhere from nothing to $16,400. State support for salary increases is in limbo.