This is the first part of a series on the mental health struggles of today’s generation of teenagers, the urgent need for more support in schools and how families can get help.

Schools scramble to keep up

The plan, Erica Jennejahn recalls, was to get ahead of things, to meet with small groups of students and talk about resolving conflicts and sharpening social skills. That was last summer.

Then school started.

The very first week of classes brought what she described as “explosive situations” at Rappahannock County Elementary School.

“We had to jump in right way,” said Jennejahn, the social worker for Rappahannock County Public Schools. “We were drinking from a fire hose.”

Any notion of a methodical, preventive approach to addressing student mental health concerns, which had been escalating since the pandemic, faded quickly.

RCPS Assistant Superintendent Carol Johnson, left, talks with the schools’ social worker, Erica Jennejahn. After “explosive situations” at the elementary school, “we had to jump in right way. We were drinking from a fire hose,” Jennejahn said.(Photo/Luke Christopher)

Jennejahn and her team of two counselors and two behavior specialists got down to work and began meeting with students individually. They did manage to work in some group sessions but ended up interacting individually with almost 120 students from both the high school and elementary schools, or 16% of the student population. It was a 20% jump from the previous year.

But the situation in Rappahannock during the 2023-24 school year was hardly unique.

“We’ve been overwhelmed,” said Deborah Panagos, a lead social worker in Fauquier County Public Schools. “There’s always been a need to provide mental health support in schools, but post-COVID, it’s skyrocketed. I think there’s probably not a person in the school community who wouldn’t agree with that.”

Russell Houck, executive director of student services at Culpeper County Public Schools. (Photo/Emily Oaks)

Russell Houck, executive director of student services at Culpeper County Public Schools, also is troubled. “The level of optimism and hopeful thinking is lower with today’s students,” he said. “This is a generation that’s largely unhappy.”

‘More intensive cases’

The struggle with anxiety and depression among today’s adolescents is well-documented. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Teen National Health Interview Survey, completed in December 2022, found that one out of five kids between the ages of 12 and 17 said they had experienced symptoms of anxiety in the past two weeks, and 17% said they had symptoms of depression. Girls were more than twice as likely to report those feelings than boys.

Even more concerning, according to the CDC’s 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 22% of high school students nationwide said they had considered suicide. Ten years earlier, it was 16%.

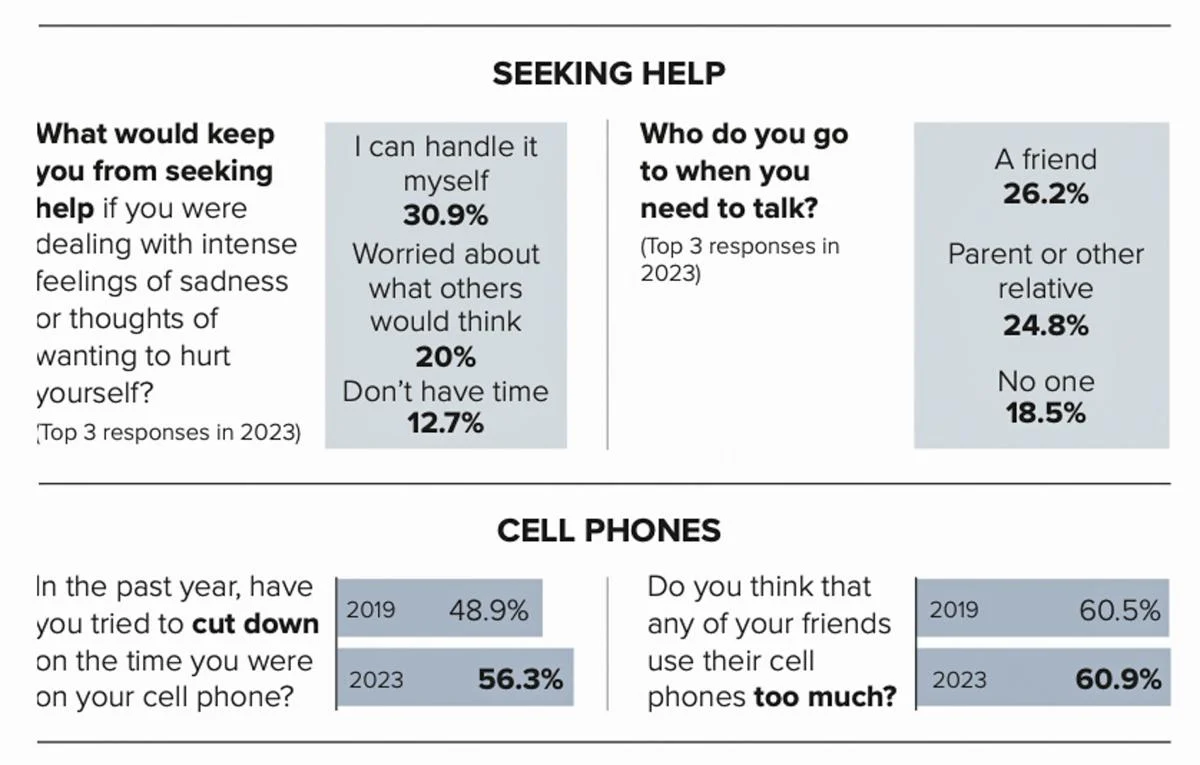

The numbers are even higher in this region. The most recent survey by the national Parent Resource Institute for Drug Education (PRIDE), taken last fall of 4,274 middle and high school students in Fauquier and Rappahannock counties and released last month, revealed that 43% said they had struggled with anxiety and 29% with depression. And more than a quarter said that at least once during the previous 12 months they had thought, “I wish I were dead.”

One bright spot is that the anxiety percentage rose only slightly and the depression percentage is lower than the last PRIDE survey in 2019. Nonetheless, both the anxiety and depression percentages are roughly twice what they were in 2015.

Another positive trend, according to the PRIDE survey, is a drop in substance use. Ten percent of Fauquier and Rappahannock high school students said they had consumed alcohol in the past month. That figure has been declining steadily since 2004, when it was 62%.

Renee Norden, executive director of the Mental Health Association of Fauquier County, pointed out that the rate of teenage drinking in the country began dropping in the 1980s, not long after Mothers Against Drunk Driving became active. But it has taken longer to fall off in rural communities than in urban ones for a number of reasons. Among them, there are more limited social and recreational activities in rural areas and parents of rural teens are more likely to consume alcohol as part of their social lives, according to research.

The percentage using marijuana also dropped slightly, to 8.4%, but, as with alcohol, more girls than boys said they had used it.

In Culpeper County, where students fill out the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey instead of the PRIDE questionnaire, the results have been more disturbing – although the most recent survey was in 2022. Then, 65% of the students said they had experienced “extreme anxiety,” compared with 53% in 2017. Responses about feeling “sad or hopeless two weeks or more” and “seriously considered attempting suicide” also climbed – from 32% to 45% for the former, and from 16% to 23% for the latter.

“We are seeing more higher mental health behavior needs than we have in a long time, particularly in the last four years,” said Carl Street, vice president of behavioral health services at Youth for Tomorrow, a regional nonprofit organization that provides therapy and counseling for at-risk teens and children. “The number one thing we’re seeing is anxiety. You would think that as we’ve come out of the pandemic, it would reduce, but it’s not slowing down.”

Taisha Chavez, director of children’s services at the regional nonprofit agency Encompass Community Supports, agreed. “There definitely are more intensive cases now,” she said. “It’s become more of a struggle to connect families to the right services.”

Fewer therapists

The increase in more serious cases comes at a time when access to mental health professionals is shrinking, especially in rural areas. COVID-19 seemed to have had a big impact, particularly among therapists who work with families of distressed children. Some retired; others chose to go into another line of work.

“It used to be that if I was in a meeting and saw there was a need for counseling or therapy for a child, I could, by the end of the meeting, give the parents the names of three or four people they could call,” said Tracey Sasso, a longtime social worker in the Culpeper school system. “You can’t do that now.”

And that shortage can result in younger, less experienced mental health providers taking on challenging cases, according to Amanda Long, director of the Culpeper Youth Network, a county agency that works with at-risk youths and their families.

“We’re definitely seeing higher-need situations than in the past, kids who need seasoned people working with them and their families,” Long said. “But those who are available aren’t so seasoned.”

School districts in the region are trying to compensate by adding to their mental health teams.

In Rappahannock, for instance, the district recently hired a “transition coach,” Krista Riggelson, to bolster its staff of Jennejahn, a school psychologist, two counselors and two behavior specialists. The goal, said Jennejahn, is to have the transition coach take on the bulk of the individual counseling with students.

Fauquier schools has added two more social workers to its staff for the coming year. In Culpeper, the school district will have at least one “behavior interventionist” in each school, part of a “student wellness” strategy in response to the results of the 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey.

Fauquier County Public Schools’ Deborah Panagos with her dog Charlotte, who is in training to be a therapy pet, are welcomed at the reception area at Liberty High School in Bealeton. She’s joined by office assistant Amy Minks, center, and Assistant Principal Christy Crocker, right. (Photo/Luke Christopher)

But efforts to beef up staff come with challenges. “It feels like a lot of people just don’t want to go into education anymore,” said Panagos, the Fauquier social worker. “We’re struggling to fill counseling positions. In the past, we never did. We used to be able to find social workers easily. Now it’s not so easy.”

Or, as Culpeper’s Houck put it: “The pipeline of people going into school psychology and school counseling is greatly diminished.”

An unsettling trend

One of the more demanding aspects of those addressing student mental health needs is responding to threats of self-harm or suicide. It has been an unsettling – and escalating – trend in recent years, particularly among teenage girls, who, data show, have higher rates of anxiety and depression than boys.

Nationally, 10% of female high school students responding to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey in 2021 said they had attempted suicide. Thirty percent of girls said they had considered suicide, up from 19% in 2011, and twice the rate of male students.

In Virginia, the number of self-harm visits to hospital emergency departments by children nine to 18 years old more than doubled from 6,520 in 2016 to 14,298 in 2021, according to data compiled by the Virginia Department of Health. That includes visits involving suicidal thoughts, self-harm or actual suicide attempts. The highest rate in 2021 was among girls 13 to 15 years old, accounting for 13% of all emergency-room visits of girls in that age range.

When a school mental health professional learns that a student has indicated that he or she is considering suicide – sometimes from the student or a teacher, but maybe a friend who has seen something posted on social media – they do a risk assessment, a series of questions to determine the level of the threat.

The parents are contacted and briefed on the situation, but if it’s felt that the risk of self-harm remains high, the family could be sent to meet with a therapist from Encompass, the social services agency, or directly to the nearest hospital emergency department, where a more in-depth screening would be done.

Although the majority of incidents concern adolescents, social workers say they are seeing more cases involving much younger children.

“Any time a student here says something like, ‘I want to kill myself,’ we have to assess that,” said Jennejahn. “So, for example, I might talk to a seven-year-old kid and what he says is, ‘This kid is making me mad and I just want him to leave me alone. I want to kill myself.’

“I have to assess that the same way as an older student who has a different level of understanding of what that means and of access to resources to harm themselves,” she added. “Our process has to be exactly the same.”

This past school year, the staff in the two Rappahannock public schools handled 22 suicide risk assessments, a decrease from 29 the previous year, but still a significant number. While there were no actual suicides, a handful of the threats involved the same students more than once.

According to the Virginia Department of Health, the number of suicides in the five-county region rose only slightly, from 144 in the period from 2008 to 2012 to 147 from 2018 to 2022. But the agency doesn’t have specific data on those involving children 18 or younger.

Reducing stigma

There’s no question that school districts, in reaction to the disturbing results of recent student surveys, have stepped up efforts to reduce the stigma around mental health conditions and suicide. They have arranged group discussions where students are encouraged to talk openly about anxiety, depression, bullying and trauma.

They have brought in speakers such as Alan Rasmussen, a suicide prevention expert at Encompass. Among his messages: Telling a trusted adult a friend is considering suicide won’t jeopardize that friendship. “I tell them their friend will be happy that they said something to someone,” he said, “because they’re in distress.”

The growing awareness among students of emotional and mental health struggles appears to be having a positive effect, according to Jennejahn. More kids are willing to “talk out loud” about anxiety and depression, and that, she said, is a big step forward.

“I see more of them willing to come and say, ‘I’m having a hard time today’ or ‘I have this issue and I don’t know what to do.’ Now, they’re willing to have that conversation. They’re learning that it’s okay to say they’re not okay.”

What parents and caretakers can do

• Nurture your relationship with your child by talking more often. Many little talks may be more effective than one big one.

• Have conversations about mental health and substance use, and use “I” statements, such as “I am concerned because I’ve noticed a change.”

• During these conversations, slow down and back up if your child looks upset or confused.

• Tell your child that you’re ready to listen to them talk about their feelings. Ask how you can help them or whether they would like to talk with someone else.

• Remind your child that it’s okay to have bad days and that discomfort is often temporary.

• Encourage your child to find something they enjoy – a sport, the arts, a new hobby – that affirms their identity and builds self-confidence.

• You’re not modeling good behavior if your reaction to stress or social situations is often substance use.

• Establish expectations, set boundaries and follow through with consequences. Reasonable limits are respectful and take into consideration your child’s age and the capacity to be responsible.

• Talk to your child’s doctor, school nurse or a health care provider about behavior or symptoms that worry you.

— Randy Rieland

Sources: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Mental Health America

What to watch for

Here are warning signs that a child may be struggling with mental health issues and may need help:

Anxiety

• Social withdrawal or fear of things that he or she used to not fear

• Having behavior problems in more than one setting (at school, at home, with peers)

• More frequent negative comments about themselves and others

• Very worried about the future and expect bad things to happen

• Experiencing repeated episodes of sudden fear for no apparent reason, sometimes with a racing heart or fast breathing

• Sudden changes in school performance

• Changes in sleeping and eating habits

• Irritability and sudden mood changes

Depression

• Showing changes in energy: being tired and sluggish or tense and restless

• Having a hard time paying attention

• Feeling worthless, useless or guilty

• Loss of interest in activities they used to enjoy

• Feeling very sad or withdrawn or easily irritated for more than two weeks

• Changes in sleep or eating habits

• Engaging in self-harm

• Increasing use of drugs or alcohol

Suicide ideation

• Taking unnecessary risks; increasingly reckless and impulsive

• Expressing feelings of being trapped, like there’s no way out

• Unexplained anger, aggression, irritability

• Self-destructive behavior

• Withdrawing from family, friends or activities once enjoyed

• Giving away prized possessions

• Seeking access to methods of self-harm (guns, pills, other means)

—Randy Rieland

Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Mental Health America, Encompass Community Supports

Where to get help

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: Call or text 988. Available in multiple languages. Also can call 434-230-9704.

Mental Health Virginia Warm Line: A peer-run line for those seeking non-judgmental support or to receive referrals for mental health services. 866-400-6428.

Encompass Community Supports: 24/7 crisis services: 540-617-0774. Children and Youth Services: 540-672-2990.

Mental Health Association of Fauquier County: 540-341-8732.

— Randy Rieland