jim abdo

Developer and longtime county property owner Jim Abdo at his home near Rock Mills.

Developer brings new ideas for his buildings

The distance separating Greater Washington from Little Washington never seemed more gaping than 10 years ago, when urban developer Jim Abdo uncorked a plan to revitalize the sleepier corners of Rappahannock’s county seat.

He used terms like “leverage” and “pulse,” language better suited to his successful projects in once-blighted or overlooked areas of Washington, D.C., than in Rappahannock, where residents bristle toward outsiders showcasing makeover plans.

A “community forum” on that last Abdo vision turned raucous and at times insulting. Anti-Abdo commentary was shushed after other residents found it uncivil. Then for weeks, residents who thought Abdo’s plans might be beneficial felt attacked by their neighbors’ emails and posts. One stepped back from active participation in Washington’s Trinity Episcopal Church after sensing hostility from other congregants.

From the archives

Pulse taken

200-plus hear Abdo’s plans, apology

Public speakers

Last Thursday’s (June 19) “Rapp Live” community forum brought more than 200 people to the Theatre at Washington. Over more than two hours, more than 30 people rose to speak, including panelists Jennings W. Hobson III, 41-year resident of the town and pastor of Trinity Episcopal Church; the town’s mayor, John Sullivan; developer and longtime Rappahannock weekender Jim Abdo, whose plans for and comments about the town of Washington in a recent Washington Post business profile ignited the controversy that led us to hold the public discussion; Rappahannock County Board of Supervisors chairman and lifelong county resident Roger Welch; County Administrator John McCarthy; and moderator Roger Piantadosi, editor of the Rappahannock News.

Letter: A mayor’s perspective

Much has been written about Little Washington this past week and I understand the concerns and the passion because all of us who live here care deeply about the special nature of our county seat. I want to offer my perspective — some history and some facts, and most of all emphasize there is a process for dealing with how buildings are used and how they look in the town.

The controversial proposal — which included a Washington branch of the popular Red Truck Bakery and an Italian restaurant — dissolved, and for the following decade, Abdo became all but invisible in Washington, Va., where his unused buildings sat dormant.

Now he’s back with ideas for the buildings he owns, and some for buildings he doesn’t. He recently bought one of the town’s saddest eyesores, the neglected and disintegrating Packing Shed on the corner of Gay and Porter streets, from his friend Jeff Akseizer. Abdo is beginning renovations, hoping to make it a small conference venue to rent out to businesses or law firms. A rotation of local artists would display their work there.

abdo pullen house

Jim Abdo explains some of the planned restoration work to the Packing Shed, one of his many properties in the Town of Washington.

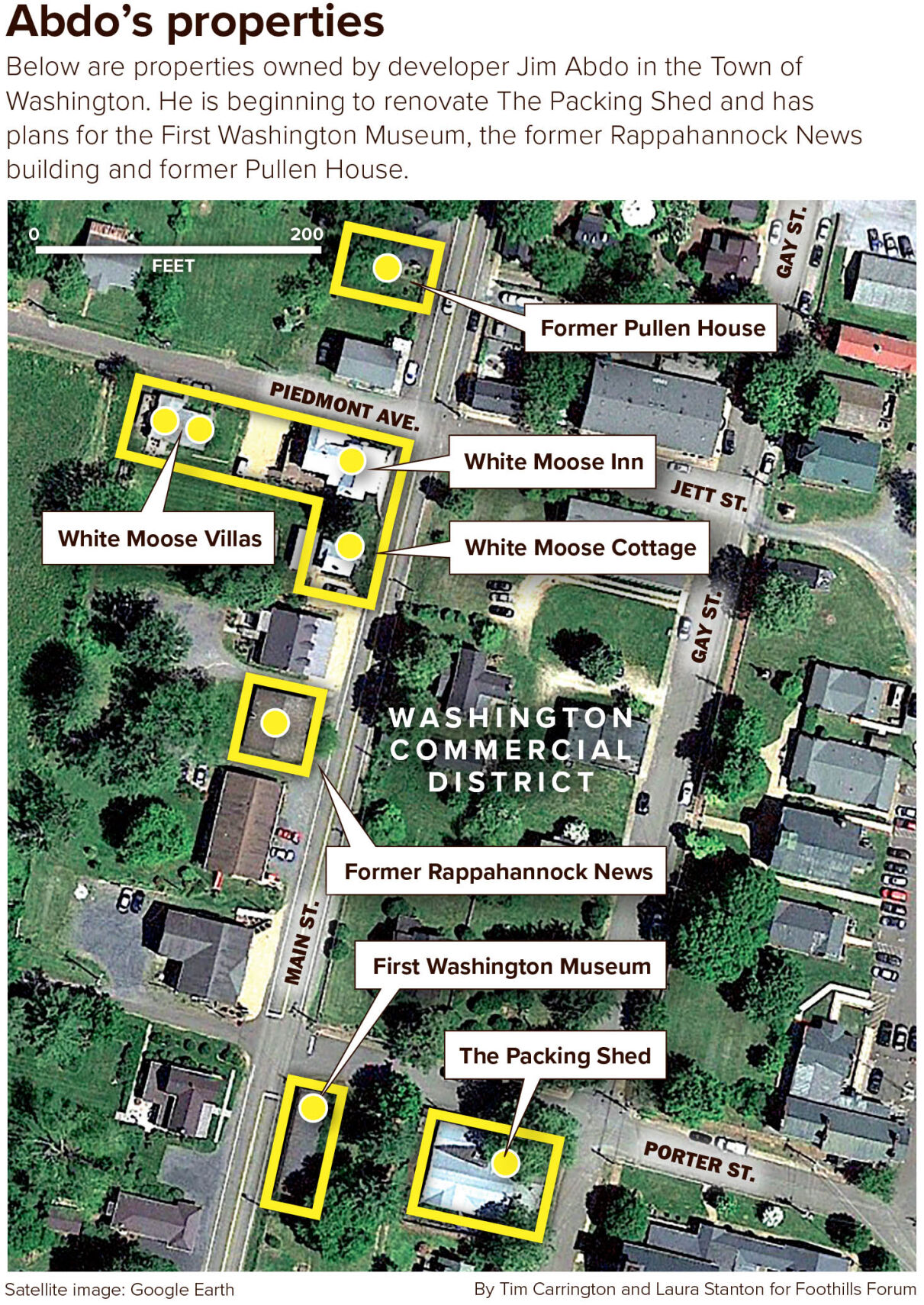

He is fashioning plans for three of his longer-held properties: The former Pullen House at 329 Main St., next to R. H. Ballard Shop & Gallery, the old Rappahannock News building further down the street, and the First Washington Museum at the corner of Porter and Main streets. Just outside Washington, he hopes to build workforce housing some day on a messy lot he bought from VDOT (the Virginia Department of Transportation) which had filled it with old buses and worn-out road equipment.

Abdo is encouraged that Washington Mayor Joe Whited has emphasized making Washington “a business-friendly place.” And while the mayor doesn’t anticipate an overhaul of the zoning structure, he predicts that Abdo won’t have to take on the public blowback or the zoning obstacles he faced a decade ago.

“We’re not going to bend anything,” Whited said, “but the environment has changed considerably in 10 years. We have a team that wants to see these buildings put to use.” For his part, Abdo is moving more cautiously, focusing for the time being on expanding hospitality options.

Even in a cautious phase, Abdo, now 64, is so passionately intuitive that he tends to see structures and streets less for what they are than for what they could become. His privately held company Abdo Development has spearheaded multiple transitions in Washington, D.C., some within depressed, crime-ridden corridors that became safer, more dynamic — and much more expensive.

In Washington, Va., Abdo’s White Moose Inn, plus a small “campus” of additional buildings, form an established part of the town. As in other Abdo adaptations, the outer structure is respectfully restored, while the interior spaces are sleek, uncluttered and decidedly up-to-date. Abdo’s other properties are investments waiting to realize their potential.

He has clear ideas about the properties, but no appetite to replay the last shouting match. Rather, he hopes Washington’s Planning Commission and Town Council will eventually free any and all investors to pursue a defined set of “by right” commercial ventures on their properties. Currently, the ordinances demand that many proposed adaptations of buildings obtain a “special use permit,” following public hearings. “It opens a Pandora’s Box,” Abdo said, particularly when county residents living outside the town demand to weigh in during official proceedings.

On a recent walk around town, he summed up the problem this way: “The biggest hindrance to economic development, historic preservation and investment in this town is the lack of certainty in the process of moving any ideas forward.”

Abdo thinks the town should define a commercial zone in the town center, within which buildings could be allowed to accommodate any of a carefully considered range of uses: bookstores or bakeries, yes; pawn shops and vaping parlors, no. Washington’s Architectural Review Board, he believes, can dependably ward off ugly or jarring designs.

Because Washington mixes residential and commercial spaces, town officials are unlikely to forego public hearings on changes that will affect current residents.

jim abdo map

Here’s what Abdo envisions for his properties:

• The Packing Shed on Gay Street would become a small meeting center; offices, partners in firms, could use it as a convenient midweek getaway, generating business for inns and restaurants on otherwise slow days.

• The Pullen House on Main Street would be a high-end VRBO (Vacation Rental By Owner).

• The old Rappahannock News building on Main Street, once gutted to accommodate the Red Truck Bakery (which shifted its expansion to Marshall after taking stock of the pushback in Washington) could be turned into “villas,” or small housekeeping units, linked to the White Moose Inn.

• The First Washington Museum on Main Street could carve out two or three artist showrooms, with painters working on sight and displaying their work. In time, vine-covered, unused garages owned by neighbors, he imagines, could follow suit, forming a small arts district.

Abdo in town, and country

Brash and bold, Abdo can sniff out opportunities, and then make them happen. During the decade his Rappahannock properties languished, Abdo Development, his privately owned firm, added multifamily apartment structures around Washington D.C., created the Hive Hotel in Washington, D.C.’s Foggy Bottom area, and diversified with a cannabis campus and biomass processing facility, both in Maryland. The company also has invested in data centers, mostly overseas.

Abdo sits on the boards of the Old Dominion National Bank, Arena Stage and American Near East Refugee Aid. His home in the District is a renovated ambassadorial residence just off D.C.’s Embassy Row that he bought from the government of Ghana in 2000, the same year he and his wife began work on their current Rappahannock property near Rock Mills.

In the face-off 10 years ago, Abdo was typecast as the rich urban deal-maker bent on turning the Town of Washington into the facsimile of a glitzy corridor in the District of Columbia. However, the cartoon image belies the developer’s modest background in workforce housing in Kent, Ohio, where his father was employed as a tool designer.

And over 35 years of building a commercial success in bustling Washington, D.C., he and his family regularly recharged in Rappahannock County. “I love Rappahannock for what it doesn’t have,” Abdo said. “I love the fact that it isn’t the Hamptons.” Besides quiet, his property offers panoramic views and a river path, where his children — now of college age — waded and pointed at tadpoles.

abdo rock mills

Jim Abdo at his home near Rock Mills.

Abdo’s blunt, unapologetic style often sets him apart from the gentlemanly side of Virginia’s Piedmont. At the community forum 10 years ago hosted by the Rappahannock News, he boasted that “I won’t pose and act like my heritage is from the state of Virginia or that I have relatives that go back to the 1730s.”

Still, Abdo has quietly fended off various would-be renters that would have offended local sensibilities. According to his account, one wanted to open a tattoo and piercing parlor; another suggested a flea-market style emporium of household leftovers, another a warehouse of junked auto parts. One of the more persistent entrepreneurs sought to open a gun store on Main Street. “I want to protect businesses already operating in town and protect the integrity of the town,” Abdo said.

While investing in data centers, Abdo doesn’t want them in Rappahannock. At the same time, he chortles when he sees vociferous critics of data centers spending hours on devices that require them.

Town’s business balancing act

What Abdo wants for the Town of Washington are commercial investments compatible with the current ambiance and aligned with the Comprehensive Plans adopted by Washington and Rappahannock County, both of which he’s scrutinized. The benefits to the town, he said, would be “more jobs, a diversified tax base in a town heavily dependent on The Inn at Little Washington, and more users to support the water and sewer system.” Finally, employees of the new businesses would bring activity to the existing shops and eateries.

Inn at Little Washington plans transformational expansion, adding rooms, buildings and a spa

The Inn at Little Washington, soon to celebrate its 45th birthday, has unveiled a bold expansion plan that pushes the county’s largest private enterprise into new territory, and presents the Town of Washington with significant changes in its streetscape and ambience.

But Washington isn’t only, or mainly, a place to do business. ”Yes, we want to encourage business,” said Caroline Anstey, chair of the town Planning Commission, “but we must be and remain a residential town.” Residents want to weigh in not only on whether new commercial activities should materialize, but how, Anstey notes, and questions over parking, hours of operation and noise levels are considered legitimate areas of citizen concern.

Long-time resident Nancy Buntin likes having neighbors, and hates to see buildings sit empty. “The property that affects me the most is the Packing Shed,” she said. “I just want to see something done to it before it flies apart.” And broadly, she sees value in commercial investment, based on experience with The Inn at Little Washington. “I remember the town before the Inn came,” she said. “While people say what a wonderful family town it was, it was a very poor town.”

2024-07-16-FF-Abdo–3-web.jpg

Developer Jim Abdo explains some of the restoration work to the Packing Shed, one of his many properties in the town of Washington, Va.

Two significant changes may advantage Abdo’s plans, or at least make them seem less jarring. The Inn at Little Washington’s expansion would add about 30 visitors to Washington on a given day, while Rush River Commons will bring in about the same number of new residents. Abdo figures both groups would appreciate new places to stroll, eat, drink, buy birthday presents and enjoy local art — in short, the more lively commercial zone he started pushing for 10 years ago.

Ben “Cooter” Jones, the former congressman and most vocal Abdo critic in the last face-off, isn’t eager to revive the old battle, when he told Abdo, “Most of us — maybe half of us — were getting along just fine without you, Jim.” Asked about the developer’s new plans, the “Dukes of Hazzard” cast member declined to advance any argument, but said that “I fear the die is cast” to make the town different than he remembers or prefers it to be.

Currently, there is some additional flexibility for bed and breakfasts to expand if they are in zones that are mixed commercial and residential. But beyond this, Steve Gyurisin, Washington’s Zoning Administrator anticipates a methodical review rather than a dramatic reengineering of current zoning ordinances. “There will be a pretty long-term discussion with the Planning Commission and the Town Council,” he said.

Hearings around special use permits are likely to continue, and town officials emphasize that town residents’ views will be the ones given the most careful consideration, though county residents are free to come to hearings.

For his part, Abdo is philosophical, recognizing that while change-resistant instincts have softened, they remain a force. He shrugs that it may be his children who eventually harvest his various ideas for the properties in the Town of Washington.