William “Bill” Webster, director emeritus of the FBI and CIA, on the porch of his home on Hunters Road in Tiger Valley in spring 2024 when he turned 100 years old. (Photo/Luke Christopher)

Former FBI, CIA director and Rappahannock resident dies at 101

Judge William H. Webster, former director of the FBI and the CIA died last Friday at 101, and friends, policy analysts and national media began an extended reflection on his person and record in Washington.

Like other refugees from the nation’s capital, Lynda and Bill Webster came to Rappahannock County 23 years ago and found quiet, privacy and a bucolic setting in Tiger Valley to enjoy friends, family and food.

The tranquility of this couple’s Rappahannock chapter contrasted with Webster’s many fraught days in the upper echelons of government. The Missouri-born lawyer and naval officer is the only individual to take the helm of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and later the Central Intelligence Agency — steering each past damaging revelations and full-blown scandals. For both agencies, Webster led the needed reset, restoring credibility, at least until new crises hit.

Webster’s reputation for unshakable reliability is evidenced by the divergent presidents who called on him to serve: Nixon made him a federal judge; Carter appointed him head of the FBI; and Reagan named him director of the CIA. Asked if there will be other public officials so deeply trusted across party lines, David Tatel, a Rappahannock resident, guessed, “Not in our lifetimes.”

Tatel served for 29 years as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia circuit. A Clinton-appointed judge, Tatel often talked with Webster about legal affairs on the porch of the general store at Laurel Mills, where a group of once high-ranking government officials met informally.

Lynda and Bill Webster take a stroll from the pond at their home on Hunters Road in Tiger Valley in spring 2024 when he turned 100. (Photo/Luke Christopher)

A late life wish

As word of Webster’s death reached the media, expressions from friends, pundits and high-ranking government officials poured out online. Deeply researched obituary articles ran in The Washington Post, The New York Times and other national news outlets. Former FBI director Christopher Wray, issued a statement that “he was a giant — not only in the nation’s security but in the hearts and minds of all who believe in public service grounded in integrity and principle.”

The appreciations tend to be rich in admiration, sad in the hard reality of loss and wistful in the hope that there are others in the wings who might step onto the world stage with similar courage and decency.

Last October, at 100 years of age, Webster presented every member of Congress with a book entitled, “Character Matters. . . and Other Life Lessons from George H.W. Bush,” by Jean Becker, the former president’s chief of staff. In each book, Webster enclosed a letter explaining his aspiration: “With the time on earth I have remaining, I will do all I can to encourage our fellow citizens to return to the civility we once enjoyed. Yes, we disagreed on many things and should continue to do so — but without animus. My profound hope and prayer for our country is that we can return to being a people and country the world respects.”

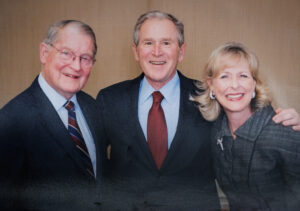

President George W. Bush, flanked by William Webster, and his wife, Lynda, sent her his condolences: “Judge Webster had the respect and confidence of several Presidents, including my father and me. His passion for the rule of law and for the greatness of America made him a model public servant.” (Photo/Courtesy)

Trust of multiple presidents

Soon after her husband died, Lynda Webster received a message from President George W. Bush. “Laura and I salute Judge William Webster, who passed away today at 101,” he wrote. “Judge Webster had the respect and confidence of several Presidents, including my father and me. His passion for the rule of law and for the greatness of America made him a model public servant.”

As a judge, Webster focused on what the law dictated, not what might find favor in the prevailing political climate. After Nixon elevated him to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in 1973, Webster issued a controversial decision in his native Missouri, ruling that the University of Missouri couldn’t deny a campus gay rights organization access to funding and school facilities. He asserted that the First Amendment’s protection of free assembly meant that the university couldn’t fence out a particular organization it found offensive. The school then petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to hear the case, but the high court declined to do so, and Webster’s ruling prevailed.

In 1977, President Carter tapped Webster to lead a troubled FBI. Tatel said Webster had been reluctant to move. “He told me it was very difficult to leave the role of a federal appeals court judge when they told him to head the FBI,” Tatel said. “But he did it, and he didn’t regret his decision.”

Mastering the art of resets

In an article following Webster’s death, The Washington Post said that at the time of his move from the appellate court to the FBI, the organization “was reeling from disclosures that agents had participated in break-ins, illegally opened the mail of people under surveillance and spied on civil rights leaders.” During his Senate confirmation hearings, Webster stated that the FBI “is not above the law,” and should not “wage war on private citizens to discredit them.”

Webster restored discipline and credibility at the FBI, the Post article said, but also set a standard for active investigation of government corruption, overseeing the Abscam operation, where fake Arab sheikhs lured U.S. lawmakers into accepting bribes in exchange for political favors. One senator and five congressmen were eventually convicted of criminal offenses, including bribery.

Webster walked into another credibility challenge in 1987, when President Reagan appointed him to lead the CIA, which was sullied by what The New York Times called “the biggest crisis since Watergate,” the Iran-Contra scandal, in which the U.S. sold Iranians U.S. weapons, at hugely inflated prices, then sent the profits to anti-communist “contras” in Central America, flouting a congressional prohibition.

In another reset, Webster fired officers involved in the covert operation, and reprimanded others who had lied to Congress or the CIA inspector general about the imbroglio.

During his days in Rappahannock, aging and no longer in government, Webster still spoke up for respect for independent judicial functions and the rule of law. During President Trump’s first term, he joined former CIA directors and deputy directors in signing a letter to The New York Times criticizing the president for retaliating against John O. Brennan, a former CIA director, by revoking his security clearances. According to The New York Times, Brennan had both criticized Trump and participated in the early stages of investigating Russian interference in the 2016 election.

Later, in a New York Times guest essay, Webster denounced “destructive” attacks on special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation of Russian election interference. He warned that “faith in the justice system and in our intelligence agencies cannot be collateral damage in a partisan grudge match.”

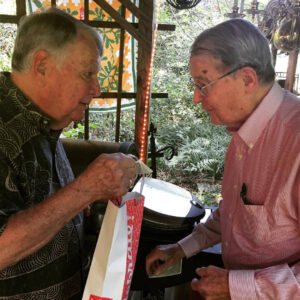

Former FBI and CIA director William Webster (right) presents a birthday gift to Col. John Bourgeois, the former director of “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band who lives outside Washington in Tiger Valley in 2017. (Photo/John McCaslin)

Friendships in Rappahannock

Never exclusively glued to newsfeeds, Webster had a gift for friendship, keeping a close connection with the late J. Bennett Johnston, the four-term senator from Louisiana who settled into Old Hollow in retirement.

Col. John R. Bourgeois, director emeritus of “The President’s Own” United States Marine Band, met Webster about 40 years ago when he was based in Quantico, Va. where both Marine Corps Base and the FBI Academy are located. Webster gave the band director and composer a tour of the FBI facility, and the two began a friendship of multiple decades. Both were members of the exclusive Alfalfa Club in Washington, D.C., whose membership is limited to about 200 influential politicians and business leaders.

Bourgeois, once he had property off Hunters Road, was on a concert tour when he learned from his house sitter that the buyer of a nearby parcel came by to say hello. He didn’t learn until his return that the new neighbor was his old friend. The two enjoyed lunches and long talks — sometimes about Washington recollections, often about books or history, sometimes about their dogs and cats, never about contemporary politics. Later Webster would arrive impromptu in his all-terrain Gator, sounding a horn to announce his arrival, and give Bourgeois time to uncork the Chardonnay.

As Webster approached his century birthday, Bourgeois began composing “The William Webster Centennial March.” The piece began in the key of F, for the FBI, and ended in the key of C, for the CIA. Webster learned of the composition moments before he heard it, in a recording offered at a birthday celebration for family and good friends. Bourgeois later premiered a live performance of his composition at the annual 4th of July concert at Avon Hall in Little Washington.

Ever gregarious, but admittedly more alone now, Bourgeois said, “I miss his wonderful reflections on American history, his subtle wit and his warm and generous personality. We have lost a great American.”

Four generations of Websters

As Webster’s hold on life weakened, Lynda kept the couple’s wide circle of friends and family informed through the listserv CaringBridge. During the final days, there were four generations of Websters, including the judge, together at the house. He is remembered as a person who would step in when his country needed him, and who could reliably put things back on track when they had gone awry.

The family has set a tentative plan for a memorial service Sept. 18 at National Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C.