Reduced health care, access to services

Rappahannock County and other rural areas are likely to be hit the hardest by cuts in Medicaid, the health insurance program that more than one in five Americans depend on.

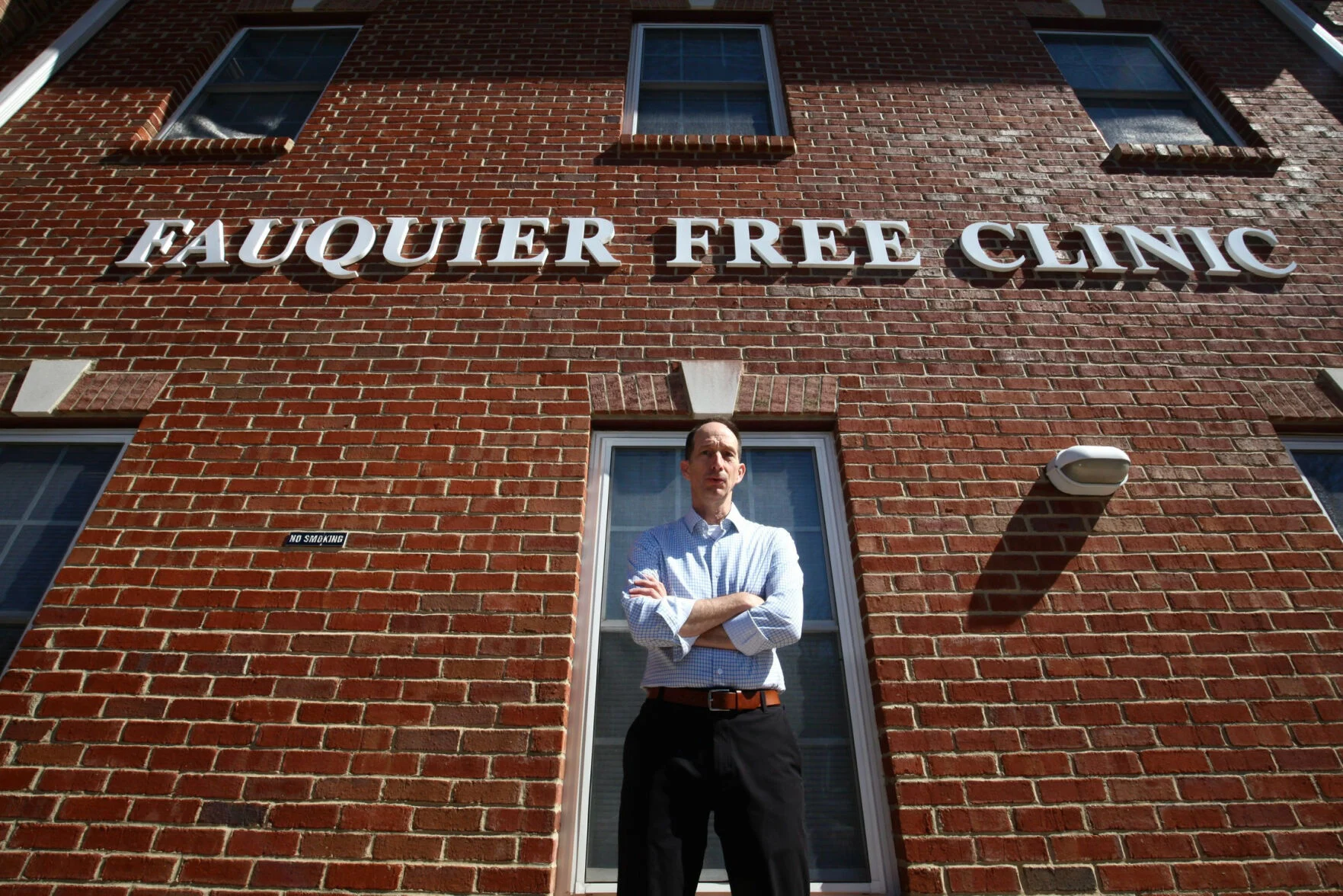

“The consensus is that between 300,000 and 400,000 Virginians will lose coverage,” said Rob Marino, executive director of the Fauquier Free Clinic in Warrenton, which also serves Rappahannock County, where 15.3% of residents, or 1,144 people, count on the program to pay for doctor visits, pharmaceuticals and longer-term treatments.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, enacted into law earlier this month, choreographs requirements expected to push millions of Americans out of Medicaid — either because they’re found ineligible under new work requirements, or because they quit, overwhelmed by the paperwork demands.

Rufus Phillips, the chief executive of the Virginia Association of Free and Charitable Clinics, called the law, “the biggest cut to the health care safety net in decades.”

One key indicator: Virginia’s Medicaid program pays for one in three births in the state.

While cuts in support for national parks, nutrition, veterans’ benefits, social services and school funding also are generating anxiety, Medicaid’s lifeline is unique: The program, signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson 60 years ago, covers 71.4 million Americans, or 21% of the U.S. population according to the Pew Research Center. Counting the counterpart program for children, it comes to 78.4 million or 23% of the population .

For many, Medicaid is all there is

In areas such as Rappahannock, with few large employers offering health insurance to workers, Medicaid is what enables many residents to receive needed medical treatment.

The Congressional Budget Office figures federal and state governments will cut outlays for Medicaid by $990 billion over 10 years. The most significant reductions — an estimated $326 billion — will flow from work-related eligibility standards, along with accompanying reporting demands on policyholders.

Policyholders who are elderly, disabled or caring for young children or ailing family members, are exempted from the work requirements and the associated reporting, but many others must update the government on their work status as frequently as every six months.

Organizations like the Fauquier Free Clinic, Marino said, will need employees and volunteers to assist with the paperwork requirements. Many current policyholders, he predicted, will be overwhelmed by these burdens, and will drop out, while others will be found ineligible.

Half the clinic’s clients carry Medicaid, which reimburses the organization for most treatments and diagnoses. Patients often need to fill prescriptions or line up follow-up treatment with a specialist, both normally covered by Medicaid. As more patients lose such coverage, the clinic will pick up the tab. “It hurts on both sides of our budget,” Marino said.

The clinic brought in $3 million in revenues last year, including $547,962 from Medicaid, government and COVID19 emergency funds. As these sources shrink, the counties can expect pressure to provide greater support. This year, Rappahannock is providing $15,000 for the clinic. Individual donations and foundations provide for more than $1 million.

Difficult choices

Cuts in Medicaid support for some users of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) will also shrink. Kerry Sutten, owner of Sperryville’s Before & After cafe, provides a compensation supplement to permanent staffers to help them acquire ACA health coverage. Under the new law, these supplements won’t buy the same level of care that they once did. The resulting choice: stick with today’s supplement, though it falls short, or expand it (and decide whether to pass the added costs on to customers by charging more for coffee and food.)

The law’s architects view the work requirements as the key to chopping Medicaid spending. For families losing their coverage, the changes mean reduced access to health care professionals and greater health risks. For providers, the law represents an expected drop in revenue.

A study published by the Annals of Internal Medicine estimated that each year, an additional 129,060 people would forgo needed medical treatment, resulting in more than 12,000 preventable deaths.

Immigrant families face special complexities. Undocumented immigrants now fall outside Medicaid, but can apply for federally-funded emergency care. Under the new law, this would be cut back.

One family now served at the Fauquier Free Clinic — not identified to avoid increasing deportation risks — presents a not uncommon mix. The parents and their eldest child, who moved to the United States without documentation, can’t tap Medicaid, while two younger children, born in this country, and are treated as citizens, are eligible. Thus, two children visit doctors and dentists, while a third, along with the parents, fall outside the frayed health care system entirely.