Federal cuts loom over providers, programs

For nonprofits and health care providers in the region — as well as the people receiving rural health services — these are troubling times.

For nonprofits and health care providers in the region — as well as the people receiving rural health services — these are troubling times.

The prospect of cutbacks in federal government funding — whether for huge health insurance programs such as Medicaid or simply hoped-for grants — has them searching to find other non-governmental support, and holding planning sessions to see what services they still could provide with considerably less money.

The cutbacks, along with mass layoffs of government employees, are part of an effort by the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), led by Elon Musk, to slash federal spending.

“I don’t think most people understand how pervasive federal funding is in the sense of going to nonprofits, going to localities, going to states,” said Rufus Phillips, CEO of the Virginia Association of Free and Charitable Clinics. “Most have not realized the extent of the ripple effects. It’s everywhere.

“Even if federal funding was only 10% of what a nonprofit takes in, every dollar matters in a nonprofit,” he added. “Take that away and you’ve created a crisis.”

‘Scrambling’ for funding

Case in point is the fledgling Rappahannock Rural Health Network (RRHN), a consortium of nonprofits, local businesses and regional health systems, such as Valley Health and UVA Health.

Last summer, RRHN, in line with its mission to improve health care services in rural communities where they are in short supply, received a $100,000 “planning grant” from the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Among other expenses, it’s been used to cover the salary of RRHN Director Bob Richey, but that grant runs out this summer.

The plan is to apply for an “implementation grant” of more than $1 million to begin moving forward on a wide range of initiatives, including expansion of the non-emergency health clinic at Rappahannock County Elementary School, improving home clinical care to reduce hospital admissions, and exploring ways for local residents to get prescriptions filled without having to drive outside the county

But that funding option may be in jeopardy, according to Joyce Wenger, president of Rapp at Home, the lead nonprofit with RRHN.

“Our chances seemed pretty good,” she said. “But now it’s totally uncertain. We’re scrambling to find non-governmental grants.”

Ripple effects

Another related grant proposal, submitted by Valley Health System, faces similar uncertainty. It is seeking funding to establish a program called Project DASH (Driving Access for Social Needs and Health) that would serve residents of Rappahannock, Page, Shenandoah and Warren counties.

“It would be a mobile van, like a mobile medical provider that would establish a regular rotation of care,” said Jason Craig, Valley Health’s community health director. “So it could be in, say Sperryville, every Tuesday or every other Tuesday.”

Ideally, the program could be expanded to include the use of “community paramedics,” Craig noted. “Say a doctor sees a patient at a mobile care unit, and they say I want to see you again in six months,” he said. “But the doctor tells them, ‘Over the next few weeks, I want the community paramedic to follow up with you to make sure you don’t have any questions about your meds.’”

Craig said he should know this summer if the grant is awarded.

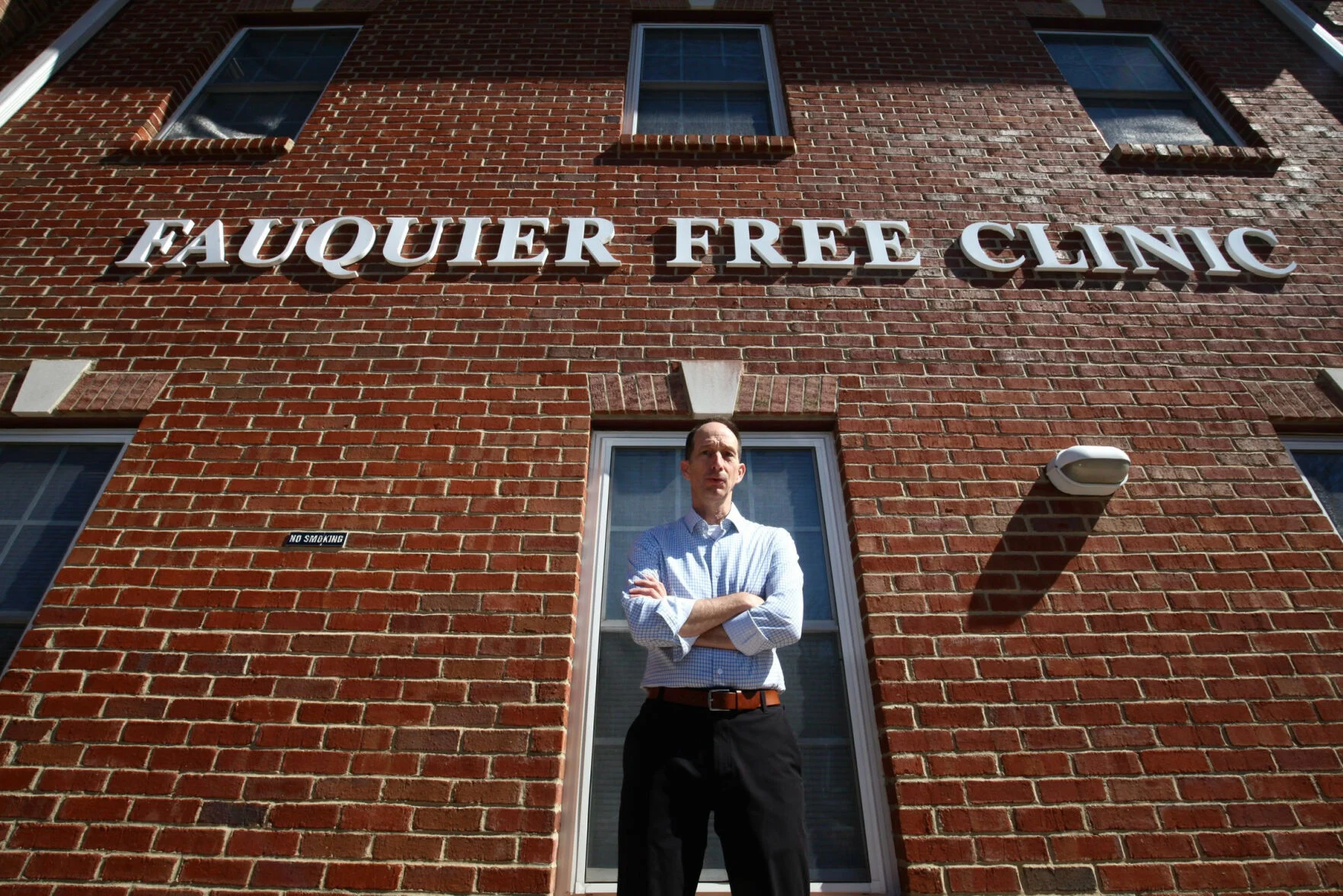

Joyce Wenger, president of Rapp at Home, on plans to seek a federal grant for rural health initiatives: “Now it’s totally uncertain. We’re scrambling to find non-governmental grants.” (Photo/Sophie McLeod)

The specter of diminished federal support is also unsettling to nonprofits like Encompass Community Supports, which provides mental health, substance use, disability, children’s and aging services for residents of Rappahannock, Culpeper, Fauquier, Madison and Orange counties.

Another aspect of rural health care that could be affected is the Transportation Collaborative Mobility Center at the Rappahannock Rapidan Regional Commission. It works with area nonprofits to find volunteer drivers to take elderly or disabled people to medical appointments.

Kristin Lam Perazza, director of Regional Mobility Programs and Partnerships, estimates that about three-fourths of the Mobility Center’s budget comes through Federal Transit Administration funds passed through the state. She said “mitigation” discussions have already begun.

“There has been an incredible amount of changes happening very quickly,” she said. “And having the focus being pulled away from vulnerable populations is a theme with a lot of changes we’re seeing.

“We’re looking at our priorities and asking what’s the worst case scenario. What if we get a 25% cut? What would a 75% percent cut look like?”

Lam Peraza thinks most of what the center does is scalable, but she is worried about possible ramifications for its nonprofit partners. During a recent discussion, she was surprised to hear one express concern about a potential drop in donor support.

“We asked what they meant and they said that a lot of their donors were older, retired adults, and they have children who work for the federal government,” she said. “They pointed out that they’re less likely to donate if they have to help out their adult children who have lost their jobs.”

Cutting Medicaid?

Then there’s the matter of Medicaid — specifically whether it will be a chief target in the effort to dramatically reduce federal government spending.

In a recent interview, President Donald Trump said, “We’re not going to touch it. We’re going to look for fraud.” At the same time, however, a budget outline adopted recently by House Republicans calls for the House Energy and Commerce Committee to cut spending under its jurisdiction by $880 billion over 10 years. According to analysis by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, that would be very difficult without dramatically shrinking Medicaid funding.

More than 1.7 million Virginians are now enrolled in Medicaid. More than one-third of that total has gained Medicaid coverage since the program was expanded in the state under the Affordable Care Act in January, 2019.

Locally, 1,864 people last year — about 25% of Rappahannock’s residents — received Medicaid, SNAP (formerly known as food stamps) Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) benefits, or some combination of the three. For Culpeper and Fauquier counties, those totals were 17,530 (33% of the population) and 14,724 (21%) respectively.

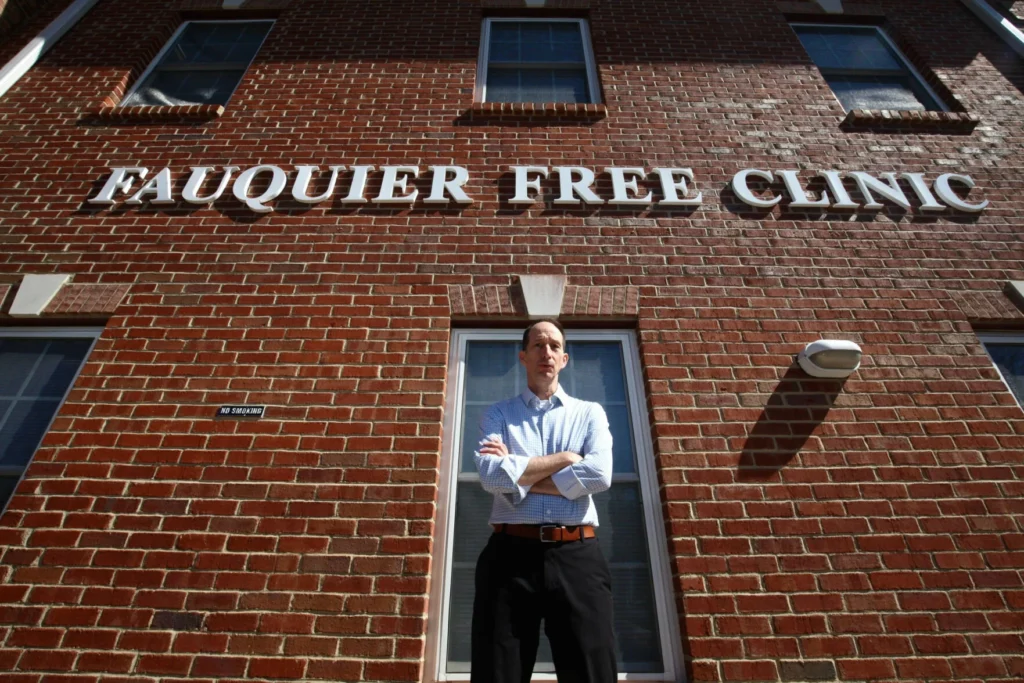

Rob Marino, executive director of the Fauquier Free Clinic: “If suddenly Medicaid is taken away from someone we’re seeing, we will continue to see them,” (Photo/Sophie McLeod)

“If there’s a significant cut in Medicaid, there will be immediate consequences in Virginia, that’s for sure,” said Rob Marino, executive director of the Fauquier Free Clinic, one of the relative handful of free medical clinics in the state that accepts Medicaid patients.

“If suddenly Medicaid is taken away from someone we’re seeing, we will continue to see them,” he said. “But in addition to the fact that we’re no longer going to get paid for seeing that patient, when we send them out to get their Prozac or their diabetes medicine, we’re going to get the bill for that. It would get us on both sides.”

Another potential consequence, he said, would be a flood of patients into hospital emergency departments.

“People who have lost their Medicaid are just as likely to be sick, and maybe more likely, because they won’t be getting as much care or as quickly,” Marino said. “If they go to urgent care, they’re paying out of pocket. If they go to the emergency room, they’re paying out of pocket or not paying.

“That costs the hospitals because they have to stabilize people,” he added. “I don’t think anybody would be against that, but it’s costly. And, we’ll be back to the bad old days when people were ruining their credit over things that are not that complicated to fix.”

The loss of health care coverage also can lead to a downward spiral, noted Gail Crooks, director of Rappahannock’s Department of Social Services. Often people who qualify for Medicaid work in jobs where they don’t get sick leave, and if they miss much time, they’re more likely to be fired. And that, she said, can put their housing situation at risk.

“There’s this song that says that there are many roads to rock bottom and few roads out,” Crooks said. “The stress just builds, and when people are under stress, that’s when poor decisions are made. Bad financial decisions. Bad relationship decisions. Bad discipline decisions.

“When people lack security and stability, it can have a very far-reaching effect.”