How engineers are making it fit for development

For many in Rappahannock County, the approval process for Rush River Commons was the main game. But behind the scenes teams of engineers already were busy, wrangling with their own major task: how to build on a site that any for-profit developer in their right mind likely wouldn’t touch.

2023-08-Rush-River-Redi-Rock–2-web.jpg

A worker positions a Redi-Rock block, which weighs between two and four tons depending on its size.

Complex doesn’t begin to describe the 5.1 acres at the corner of Leggett Lane and Warren Avenue, on which the Town of Washington’s first mixed-use development is under construction. As explained by project manager Steve Plescow, it’s a wetland, a complex floodplain with soil that is too weak to develop sturdy foundations without additional support.

2023-08-Rush-River-Redi-Rock–7-web.jpg

Rush River Commons project manager Steve Plescow and site manager Richie Burke

The 242,000 square foot development will be home to the Rappahannock County Department of Social Services, Rapp at Home and the Rappahannock Food Pantry, a structure that project organizers say should be habitable by next summer. Space for a cafe or restaurant and 18 apartments also are part of the plan.

The challenges presented by the unique site are costly to address. Convoys of trucks hauled 23,000 tons of dirt, donated by a Culpeper quarry, to sit atop the poor soil, to anchor a complicated retaining wall that will prevent flooding — a “highly unusual” move for a project of such small scope, said Tim Hoerner IV, another project manager.

While none of the challenges themselves is atypical, managing a confluence of them on such a small site, while being sensitive to the environment, makes the project unique, engineers said.

Located at the town gateway, the site might be seen as prime real estate. But a for-profit developer, bent on maximum return on investment, likely would not put up the steep resources required to construct what are relatively modest buildings on such an intricate, small plot so remote from any major population or commercial center.

“The DNA of a property is its developability,” said Hoerner, a real estate developer and investor based in Annapolis, who oversees the project’s costs and commercial and residential leasing.

“Why this project is unique is: It’s way out in the countryside. It’s extremely expensive to develop and it was still developed despite all these, what I would say, challenging characteristics, because of the generosity of the Sherwood Fund,” Hoerner said, referring to a foundation owned by local resident Chuck Akre, which is funding the project.

Plescow, a career civil engineer in Northern Virginia who has done municipal and commercial work since the late 1970s, said Rush River Commons was among the most complicated he’s worked on, because of the tricky site conditions.

“Truly, one of the greatest things about working on this project, and being part of the team, is being able to help the community,” he said. “You don’t get a lot of this type of project, so [I’m] lucky to be on it and helping.”

Sign up for Rapp News Daily, a free newsletter delivered to your email inbox every morning.

The beating heart of Rush River Commons’ existence is philanthropic backing by Akre, who funds the project on his own dime, in what he described as an effort to give back to the community. Hoerner said: “They were willing to spend more money to make sure that it went back to the community that they live in — that’s pretty spectacular.”

The Washington property was the only site Akre seriously considered because it was close to home, Hoerner said. But ‘home’ is the Town of Washington with its own regulations and politics; and it’s likely were a similar project proposed in the county, it would face greater pushback from officials and residents alike.

“A for-profit developer would look at this and say: ‘Thank you, no,’” Plescow said, evidenced by the fact that for decades the site sat vacant. Commercial developers also are looking to cut costs and speed up construction timetables in the name of turning a quick profit, which Plescow said they’ve avoided at Rush River Commons because money-making is not a motive.

“Thank goodness we’ve got Chuck and the foundation that look at it a different way,” he said. “They look at it as more of a civil, philanthropic project.”

Akre said when he bought the property he was unsure what its use would be, but residents voiced support for affordable housing and community space. “The site really was basically unbuildable except for the work we did,” Akre said. “It would never have been done for a profit basis. The cost would just be too astronomical.” He declined to disclose the site’s preparation costs.

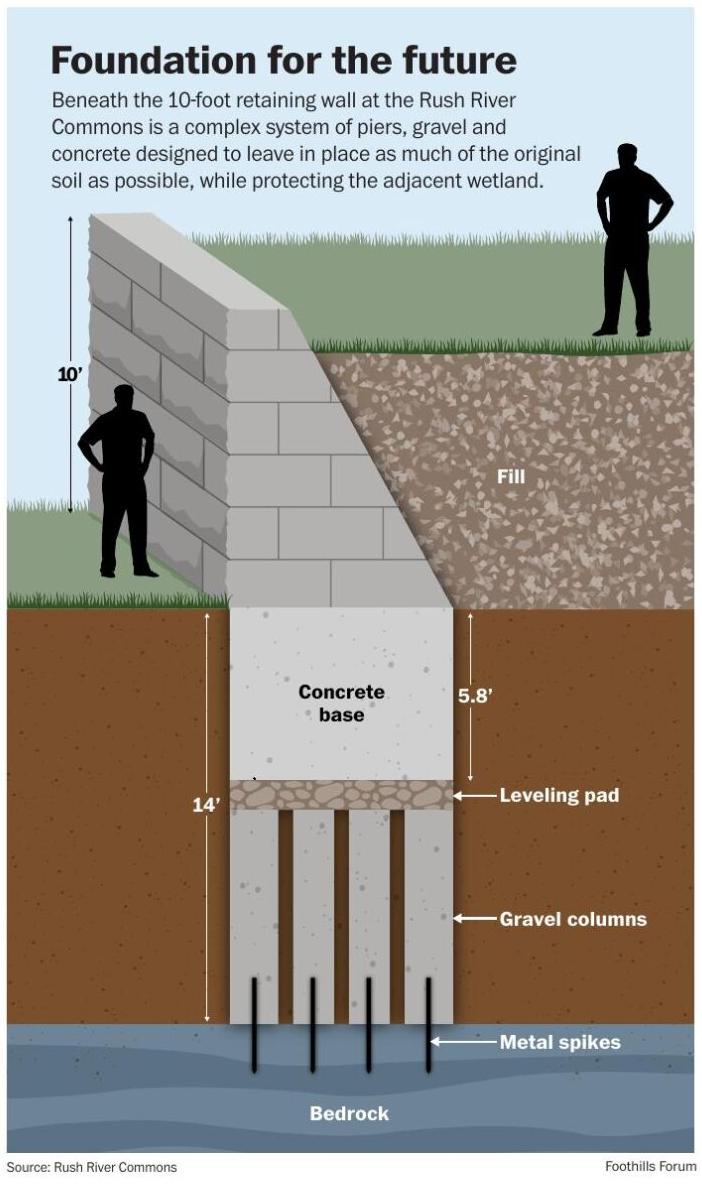

The site is surrounded by two town roads, a wastewater treatment plant and a stream that runs on its east side. Because of its small size, they’re building a retaining wall along the stream to have the buildings above a level at which severe, once-in-a-century flooding could pose a fatal threat. The wall was the first structure built to protect work on the site from summer thunderstorms.

“It basically armours that side of the site and protects it from eroding away,” Plescow said. “And it also gives us a very hard line against the wetland areas, so we don’t encroach into them.”

Engineering.v3-14.pdf

Because the site is in a stream corridor, there’s been an accumulation over time of very fine soils that provide little strength. The good news is bedrock under the site is close enough to the surface to help stabilize the soils when the retaining wall is finished.

As explained by Plescow, they could have dug out all the soil above bedrock and replaced it with better dirt to provide a stronger foundation. But that would have been time consuming, expensive, and not very environmentally friendly, because of the need to find a place to dispose of so much displaced dirt.

Instead, metal spikes, characterized as nails, are drilled into the bedrock to hold two-foot thick concrete beams, which become the foundation for the Lego-like retaining wall. Rising to about 10 feet, the retaining wall only will be seen from the stream side of the site.

2023-08-Rush-River-Drilling–5-web.jpg

The metal pipes are drilled about 5 to 8 feet into the bedrock until they refuse, then filled with cement and rebar for reinforcement. They are placed about every eighth feet and referred to as ‘micro piers.’

Behind the wall, stone-like columns go down to bedrock, pushing down soil, which is then displaced with gravel. “It makes like a column of stone into the ground,” Plescow said. A pattern of these columns across the site will stabilize the ground, dispensing with any need to remove soil.

Also under the site, a stormwater management container will collect runoff. Storing the water, instead of releasing it immediately, will protect stream health by allowing chemical pollutants to break down before the runoff is released back into the stream.

2023-09-01-RRC-Cement-Pouring–13-web-2.jpg

Pouring cement for the Food Pantry foundation at Rush River Commons earlier this month.

The stakes are high because the project will be in plain sight of anybody entering town. “We do something wrong, everybody’s gonna see it for a very, very long time,” Plescow said.

The willingness of stakeholders to work together to get Rush River Commons over the finish line was “refreshing,” after experiencing so much tumult over projects in communities elsewhere, he said.

“I truly think that people are going to be very happy when we finish the construction of phase one” because people will feel like they had ample input in the project, Plescow said.

Chuck Akre’s Fagus Foundation is the largest donor to the independent, nonpartisan nonprofit Foothills Forum. This reporting complies fully with the nonprofit’s gift acceptance guidelines. No one from the Akre family or the Fagus Foundation had any role in the preparation or pre-publication review of this story.

Foothills logo – horizontal

- Foothills Forum is an independent, community-supported nonprofit tackling the need for in-depth research and reporting on Rappahannock County issues.

- The group has an agreement with Rappahannock Media, owner of the Rappahannock News, to present this series and other award-winning reporting projects. More at foothillsforum.org.