Densely populated mountain village occupies niche in county

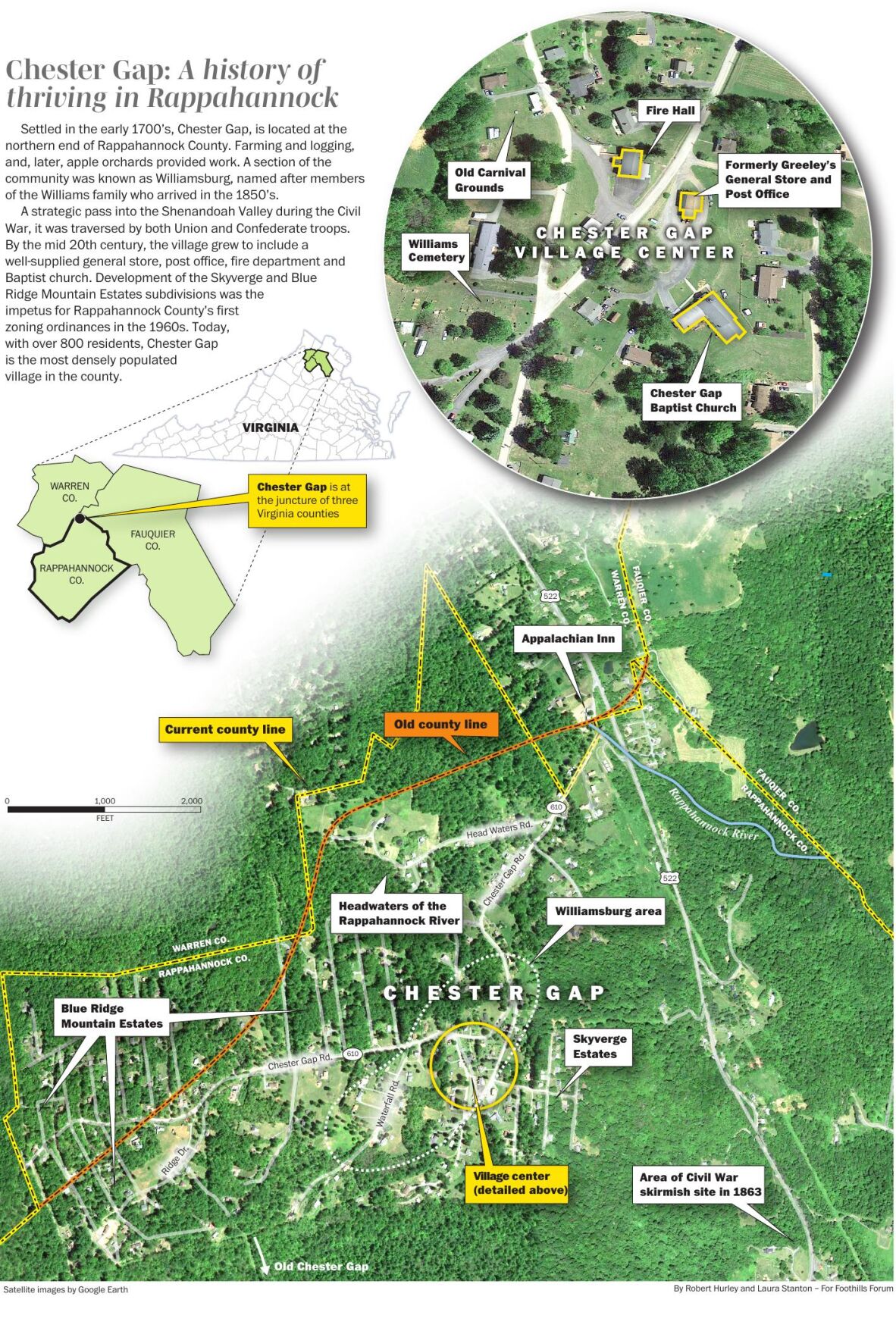

It is the most densely populated village in Rappahannock County. It has its own voting precinct. It adjoins Shenandoah National Park and is home to the headwaters of the Rappahannock River. At 1,670 feet it has the highest elevation of the county’s villages, thereby experiencing its own harsher weather.

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-Morris_Ronnie-31-2.jpg

The ‘Gap’ today: The fire station and old country store and post office.

It has more than 800 residents and about 300 homes. But with no shops or stores, and just one road in and out, chances are residents who live elsewhere haven’t spent much time in this corner of the county.

Chester Gap – or “The Gap,” as many residents call it – snuggles up to the mountains where the boundaries of Rappahannock, Warren, and Fauquier counties meet. Its main thoroughfare, Chester Gap Road, runs from U.S. Route 522 west to a dead end at a Shenandoah National Park (SNP) trailhead.

Newer residents and those whose families date back generations love the place. Housing is more affordable, they say; neighbors look out for each other; and access to services like groceries, medical care, restaurants, and entertainment, including a movie theater and bowling alley, are in Front Royal, just five miles down the north side of the mountain.

Trey Williams, with his wife Tiffany Matthews and two daughters, moved to a house on Skyway Lane in 2017. “We looked to purchase a place in the area for about three years,” he said. “We were looking for an area that we liked, had good schools, and a home we could afford. Finding that trifecta was difficult.”

Tiffany-Trey.jpg

Tiffany Matthews and Trey Williams last Octover

Tiffany, who serves on Rappahannock’s nonprofit Family Futures board and advises the county social services department, added: “One of the benefits of living here is you have the option to go to close-by Front Royal for services, but also participate in school and social activities in Rappahannock.”

A key Civil War throughway to orchard powerhouse

Little has been written about the history of Chester Gap. Once inhabited by the Manahoacs, a Native American tribe, the village’s European settlement dates to the mid 1700s when Thomas Chester purchased land on the western edge of what now is the village. Chester, who began a ferry across the Shenandoah River near Riverton in the 1730s, was considered a founding father of Front Royal.

Over the years, a road was built from the ferry along current Route 522 to what was then known as “Chester’s Gap,” and eventually into Rappahannock County. An old highway toll house that stood along Route 522 near the top of the mountain was moved in 1995 to a private property in nearby Huntly.

ChesterGapFinal.v3.pdf

During the Civil War, Union and Confederate armies fought for control of gaps in the Blue

Ridge Mountains that led into and out of the strategically important Shenandoah Valley. Chester Gap was a key access point. During the war, soldiers from both sides camped in the area.

The first notable use of the pass was in July 1862, when Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ corps of the Union Army of Virginia marched from Winchester through Chester Gap en route to its monthlong occupation of Rappahannock County.

At the time, Annie Gardner, who lived just below Chester Gap near Front Royal, observed in her diary:

July 5, 1862: “Cavalry went over toward Flint Hill this morning early, been coming back in small companies all the morning, have heard no news from Front Royal, suppose no fighting there as the Yankees look as consequential as ever.”

July 7, 1862: “Yesterday they (Union troops) drank up all the milk in the spring house, and took some of Pa’s hay this morning, they have been all over the yard, in the spring house, in the meadow, up the Cherrie trees, almost broke them to the ground…”

Almost a year later, in June of 1863, more than half of Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia passed through Chester Gap on its way north to the Battle of Gettysburg. A few weeks later, after the Confederate forces lost that battle, Lee’s army retreated through the gap. Union forces tried to block Lee’s army on the Rappahannock County side of the pass, but were pushed back by Confederates in a 26-hour skirmish on July 21-22.

Longtime residents remember old family stories of subsistence farming, logging, and blacksmithing. Two large families, the Williams, and the Wines, migrated to Chester Gap in the mid-1800s and many of their descendants still live in the village. At one time, there were so many members of the Williams family living in the area, the community became two settlements: Chester Gap and Williamsburg.

Big apple orchards were planted in the early 1900s, most notably by the Wood and North families. The Wood orchard, near the end of Waterfall Road in the old Chester’s Gap, provided seasonal work for many locals. Covering almost 1,000 acres, it had its own store, private homes, and numerous storage and processing facilities.

Ronnie Morris, whose Williams family lineage goes back five generations, said that those who didn’t work in the orchards found jobs in Front Royal. “A lot of folks worked in Front Royal at the old American Viscose Corp. manufacturing plant or the horse breeding remount depot run by the U.S. Army,” he said. “Most everybody had several acres for a garden and a few animals like hogs and cows.”

Chris Ubben, a descendant of the Wines family, represents the area on the Rappahannock County School Board and is a deputy sheriff. He recalled: “It was a little slice of Appalachia up there back in the day. It was a small, tight-knit community and folks made do with what little they had.”

A community leader from ‘The Gap’ paves way for county zoning laws

By the mid-20th century, Merritt Greeley, a resident of Front Royal, purchased land around what was then the Williamsburg area. Originally from Iowa, Greeley was a great, great grandson of Horace Greeley, founder and editor of the New-York Tribune newspaper, an ardent abolitionist and an organizer of the Republican Party.

“He got the community together,” said Morris. “Mr. Greeley built a general store; got our first post office in 1954; helped form our first citizens’ association; organize the volunteer fire department in 1960; and donated land for both the fire department and the Chester Gap Baptist Church.”

When the post office was established, it was agreed to officially name the area Chester Gap. Greeley served as the first postmaster and operated the post office out of his general store, where he kept a small room with a bed.

“In those days postmasters were required to live in the towns where they served,” recalled Morris. “But I’m not sure he stayed there very often. He’d let us kids sit in that little room and watch a small black-and-white TV he kept there. It was the first TV I ever saw.”

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-Morris_Ronnie-29.jpg

Ronnie Morris: His Williams family lineage goes back five generations.

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-Morris_Ronnie-9.jpg

Ronnie Morris’ collection of historic photos of Chester Gap

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-Morris_Ronnie-6.jpg

Merritt Greeley: Pictured at right, he served as the first postmaster. His general store, below, housed the post office. Greeley is standing with Kerry Williams, father of twins Mattie Frazier and Jesse Wines.

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-Morris_Ronnie-4.jpg

The old General Store

Greeley also owned an apple orchard near his general store. In the mid-1950s he converted it into the village’s first residential subdivision, Skyverge Estates, which comprised about 70 lots.

As other open spaces were subdivided in the 1950s and 1960s, the village began its slow transformation into more of a residential neighborhood.

A few years after the Skyverge subdivision, the Blue Ridge Mountains Estates, with about 400 lots at the top of the mountain, were carved from old orchards and woods bordering SNP. But these were little lots, some just 60 feet by 60 feet, and were marketed primarily to urban dwellers as campsites. Because they were so small, people seeking to build permanent homes needed to buy adjacent lots to have room for wells and septic fields.

“Growth kept coming,” said Hubie Gilkey who represented Chester Gap on the county Board of Supervisors (BOS) from 1980 to 1998. “First there were a few small seasonal places, then folks started building permanent homes. All those lots were going to suck water out of the ground and then put sewage back in,” he said.

“All this potential growth was a cause for concern since there was no subdivision or zoning ordinance in the county at the time. What was going on in Chester Gap was a big driver for the adoption of Rappahannock’s first zoning ordinance in 1966.”

A plane crash and a boundary change

Before 2002, the boundaries of Rappahannock, Warren, and Fauquier counties cut through Chester Gap, splitting parcels and creating confusion among residents.

In 2001, the three counties filed a petition in Rappahannock Circuit Court, stating that the uncertainty “resulted in real and personal property being taxed by a County other than the County where the property is located, in children attending school in a County other than the County in which they reside, and in confusion as to jurisdiction in the investigation and prosecution of criminal matters, the application of zoning and subdivision laws, and the proper place for the recordation of deeds.”

According to Peter Luke, Rappahannock County’s attorney at the time, government officials didn’t know for sure which property belonged in what county and which was the proper taxing authority. “The county revenue commissioners from the three counties would get together and decide who was going to tax what property,” he said. “It worked, but in my view, wasn’t the best process.”

Sign up for Rapp News Daily, a free newsletter delivered to your email inbox every morning.

Luke, who had to continually resolve questions over voting locations, law enforcement jurisdiction, zoning, and other local government issues, was the driver behind drawing a new boundary. “Although dealing with those issues was time consuming, the tipping point for me was a tragic plane crash that killed a whole family in Shenandoah National Park.

“No one knew for sure in which county the crash occurred and who had jurisdiction over it,” Luke said. “I figured it was high time we got the boundaries straightened out for once and for all.”

subtext

The boundary adjustment process began in 1997 and ended with a proposal that virtually all of the Chester Gap village area be located in Rappahannock County. The Board of Supervisors adopted the changes in November 1999, and the new boundary line eventually was approved by the circuit court in 2002.

‘You don’t get connected now the way we used to’

For decades community life in Chester Gap centered around the fire hall, the general stores, the post office, and the Baptist church.

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-Left-Wines_Jessie-Right-Frazier_Mattie-3.jpg

Sisters Jesse Wines and Mattie Frazier, whose family has lived in Chester Gap for generations.

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-twins-5.jpg

Mattie Frazier’s crown

“We started the fire department in 1960,” said Maybelle Gilkey, who served as the department’s treasurer for twenty years. “Back then, there weren’t any federal grants, so we had to do a lot of fundraising to keep the operation running. That was a main focus of the community. The post office, the general store, and the Baptist church, of course, also provided lots of ways for folks to stay in touch.”

One of the big fundraising events was the annual fireman’s carnival. Jesse Wines, whose family lived in Chester Gap for generations, recalled: “Every summer, we’d have a carnival with rides, games, and good things to eat. It was a highlight of the summer. People came from all around.” Jesse’s sister, Mattie Frazier, was crowned the carnival’s first queen – and to this day she keeps her crown as a memento of the occasion.

Todd Brown, today’s fire chief, agrees the carnival was a big deal; he met his wife Sandra at the event in 1984. “Everybody in the community would help out baking pies, working in the kitchen, keeping the area clean,” he said. “It was a very community-oriented gathering.”

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-Brown_Todd-1.jpg

Chester Gap VFD Chief, Todd Brown

The fire department closed the carnival in 1995, around the time the county fire tax was levied. “Because of operating costs, insurance, and the fact that a lot of the older volunteers had passed on, it was becoming more and more difficult to run each year,” said Brown. “I would have preferred that we kept it running for a few more years. A lot of folks were upset they lost the carnival and, in its place, had to pay a new tax.”

More change came in the 1990s. The post office closed in 1996 and cluster mailboxes were erected around the village. Greely’s general store changed hands, finally closed in 1964, and later was converted into apartments. Other community stores opened and eventually closed – the last of them, Chester Gap Store, in 2014. New homes were constructed in the existing subdivisions, adding to the influx of new residents.

Residential growth has paused somewhat in the last two years. Of the 73 new construction permits issued in the county since the beginning of 2021, only four were for Chester Gap. Still, as new homes go up, others are sold by old timers to new residents, and the village continues to see change.

“There are so many homes now you don’t know who lives here. Folks wave or whatever, but you don’t get connected now the way we used to,” said Jesse Wines.

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-Gilkey_Maybelle-3.jpg

Maybelle Gilkey still lives across from where she grew up and was the fire department’s treasurer.

chestergap.jpg

Working at the fireman’s carnival in July 1965 were Garfield Williams, Haywood Williams, John Williams, Albert Williams, Sherman Williams, Joe Williams, Ermand Morris and Hubie Gilkey.

Maybelle Gilkey observed the lack of a central meeting place for village residents. “People aren’t able to gather around potbellied stoves or on the porches at community stores,” she said. “You can’t meet at a post office, and the community room at the fire hall was closed a while back to accommodate full time EMT staff. We have the Baptist church and youth activities, but our membership has declined from an average of about 130 people to around 50.”

‘A forgotten part of the county’

Today, the village has become something of a bedroom community with its relatively dense population and homes clustered on a close-knit patchwork of roads and lanes.

“A lot of folks who live on the mountain sort of consider it a world unto itself,” said Ubben. “Because of its location, sometimes residents feel they are a forgotten part of the county.

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-Ubben-148.jpg

“We are not landed gentry. Folks up here work hard to pay the bills and keep to themselves. Although some of the old families are still a little clannish, there is an acceptance between the newer residents and those whose family history go back generations. As long as people are decent, there is no reason to differentiate between the been-heres and the come-heres.” he said.

“It is by far the most densely populated area of Rappahannock County,” said Brown, the fire chief. “This area up here on the mountain, which is a little over a square mile, has half the population of the Wakefield district, and we provide a huge tax base for the county. We’ve had our own voting precinct for close to 50 years.”

Brown, like many village residents, worries about the condition of the roads in the subdivisions where lot owners are responsible for maintenance.

“Some of these roads are just horrible,” said Brown. “They are rutted, have deep ditches, and are a real hazard. Try taking one of these fire trucks down one of these roads. It is a real challenge,” he said.

A homeowner’s association for Blue Ridge Mountain Estates, long disbanded, was established in the 1960s to collect fees for road upkeep. But as Hubie Gilkey explained: “It didn’t have any bylaw requirements to pay maintenance fees, so it was toothless. If you lived on the road and didn’t want to pay your dues, you didn’t have to.”

Gilkey was on the Board of Supervisors when an arrangement was reached with the Virginia Department of Transportation to begin paving the roads. “VDOT started to take them over, maybe did one or two roads, and then the funding played out so the project just stopped,” he said.

Today, the situation leaves homeowners to fend for themselves, with some going door-to-door, asking neighbors to chip in for road repairs.

“We have had conversations with our neighbors, but it is really difficult to get folks organized to take charge of road repairs, especially if they are absentee landlords or just own vacant lots,” said Sheila Lamb, who lives in Blue Ridge Mountain Estates. “On our road, two or three families pay thousands of dollars for maintenance but we aren’t the only ones who use it. We are subsidizing others,” she said.

Lamb has reached out to the county for guidance on how to address the problem but with little success.

Wakefield Supervisor and Chair Debbie Donehey, who represents the village, has been trying to find a way to help. “It’s been extremely frustrating,” she said. “VDOT came up with me in 2021 to take a look at some of the roads and give a ballpark cost for repairs and maintenance. I was shocked when they said it would cost over $600,000 to just bring one short road in Skyverge Estates into conformance with VDOT standards.

“It’s not for a lack of trying, but even if we got grant money and shared the costs with VDOT, upgrading the roads would still be a huge cost for our county,” she said.

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-Brown_Todd-11.jpg

Wakefield Supervisor, Debbie Donehey (right) checks in with Todd Brown while collecting signatures for her re-election, she’s currently running unopposed.

“I know folks up on the mountain don’t always feel they have easy access to county services. That is particularly true about having to drive all the way to Flatwood or Amissville to dump their trash. I’m exploring ways to see if it might be possible for Chester Gap residents to take their trash to closer facilities in Warren County.”

Snow days

To many residents, the harsh weather of Chester Gap relative to elsewhere in the county helps to define the village’s identity.

“We have the worst, and most diverse weather in the county,” said Brown. “Ice storms, heavy snow, fog that sticks around for days, you name it. It could be snowing up here and sunny in Flint Hill.”

Conditions in Chester Gap often were the determining factor as to whether Rappahannock County schools would close in bad weather.

“It would be rainy or a wet snow down below, but up here it was heavy snow or ice, and they would close schools because of the weather in Chester Gap,” said Ubben, the deputy sheriff and member of the School Board. “Some parents in other parts of the county would complain about having their kids stay home because students who lived on the mountain couldn’t make it in.”

That changed last year when the school administration adopted a policy which now allows Chester Gap students excused absences if weather conditions on the mountain warrant.“It is kind of the compromise that keeps the schools open, while making sure our kids stayed safe. Now we can have our kids, or some of our kids, excused while everybody else is still going to class,” said Ubben.

Peace and quiet

Despite so much change, Mattie Frazier said parts of the community have retained the atmosphere of past decades. “Life in the old core part of the village around the Williamsburg area is pretty much the same. It hasn’t changed that much.”

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-twins-7.jpg

Sisters Mattie Frazier and Jesse Wines: Mattie was crowned the fireman’s carnival’s first queen 1962, and she still has her crown.

Born and raised in Chester Gap, Jimmy Williams, 77, loves the peace and quiet. “Even though you don’t know people like you used to know them, it’s a good community to live in.”

Maybelle Gilkey, the former fire department treasurer, still lives across the street from her childhood home. She summed up her feelings about the village. “My kids always said they were glad they grew up in Chester Gap. You had memories, you had family, and you were a community. Everybody knew everybody, and it was a fun place. I hope we can continue to have that kind of community into the future.”

The Appalachian Inn: ‘If you were looking for trouble, you’d find it there’

The Appalachian Inn sat on the loop of Chester Gap Road, just off of U.S. Route 522. During the 1950s and 60s, it was a favorite haunt for drinking, dancing, and the occasional brawl.

“It was a pretty rough place,” said Jimmy Williams, who lives near the now shuttered building. “If you were looking for trouble, you’d find it there.”

Local lore has it that the old county boundary line ran right through the inn. Back in the day, you could drink beer in Warren County on Sunday’s but not in Rappahannock. On Sundays, patrons would sit on the Warren County side of the inn to enjoy their brew. Others say the inn was just inside Rappahannock County, but to serve customers on Sundays, a concrete block building was constructed a few feet away in Warren County. The block structure is still there, but unfinished.

2023-04-FF-ChesterGap-Morris_Ronnie-30.jpg

The Appalachian Inn as it stands today.

Whether the stories are true or not, the place had quite a reputation. The inn was mostly patronized by family members living in the village. Dale Welch, who lives in Flint Hill and now owns the property, remembers a story his father told him. “It was the territory of the local folks. If someone from Flint Hill wanted to visit, before they could enter, they had to throw a hat through the door,” he said. “If the hat came back out it was a signal they had to move down to Front Royal to do their drinking. If the hat didn’t come out, they could go on in and have a good time.”

Maybelle Gilkey remembers going there after school. “There was a little store in there and we’d get permission from our parents to stop by and get a Coke or snack after school,” she said. “But we’d never be allowed to go near the place at night.”

Asked if she had ever gone into the inn, Mattie Frazier laughed and said, “What! And die!”

Ronnie Morris recalls peeking through the windows. “Coming home from getting groceries on summer nights we’d hear the music and see couples dancing,” said Morris. “One time my daddy had to go inside and took me and my brother. I was seven years old and had never seen a woman drink beer before. We were shocked to see that. My mama scolded Daddy for taking us in.”

Mac McGrail, who lives in Huntly, said Warren County sheriff’s deputies often were staked out near the inn. “It was too far away for Rappahannock deputies to cover, but Warren County often had a patrol car close by,” he said. “Other than Route 522, there wasn’t an easy way for the Front Royal patrons to get back to town. So, the Warren County deputies had a fine time stopping people coming out. I’m sure they had a lot of court cases.”

The building still stands but needs repairs. Welch said he didn’t have any immediate plans for its future.

— Bob Hurley for Foothills Forum

Foothills logo – horizontal

Foothills Forum is an independent, community-supported nonprofit tackling the need for in-depth research and reporting on Rappahannock County issues.

The group has an agreement with Rappahannock Media, owner of the Rappahannock News, to present this series and other award-winning reporting projects. More at foothillsforum.org.