“When I first came in 2013, there was a little bit of a sense that things were frozen. Now I see a Renaissance town, a town that’s good at a number of things — food, art, music and drama — and it’s about diversity.” — Caroline Anstey, Town Planning Commission Chair (Photo/Luke Christopher)

If Washington’s buildings form a stage set, as is often said, they would offer a perfect backdrop to a sweeping drama mixing elements of renewal, uncertainty and neglect.

For more than four decades, the tiny town has reinvented itself, as the Inn at Little Washington expanded its culinary and lodging empire, lifting some two dozen buildings from their past lives. Meanwhile, a parade of outsiders built and renovated homes for retreating, retiring or remote-working.

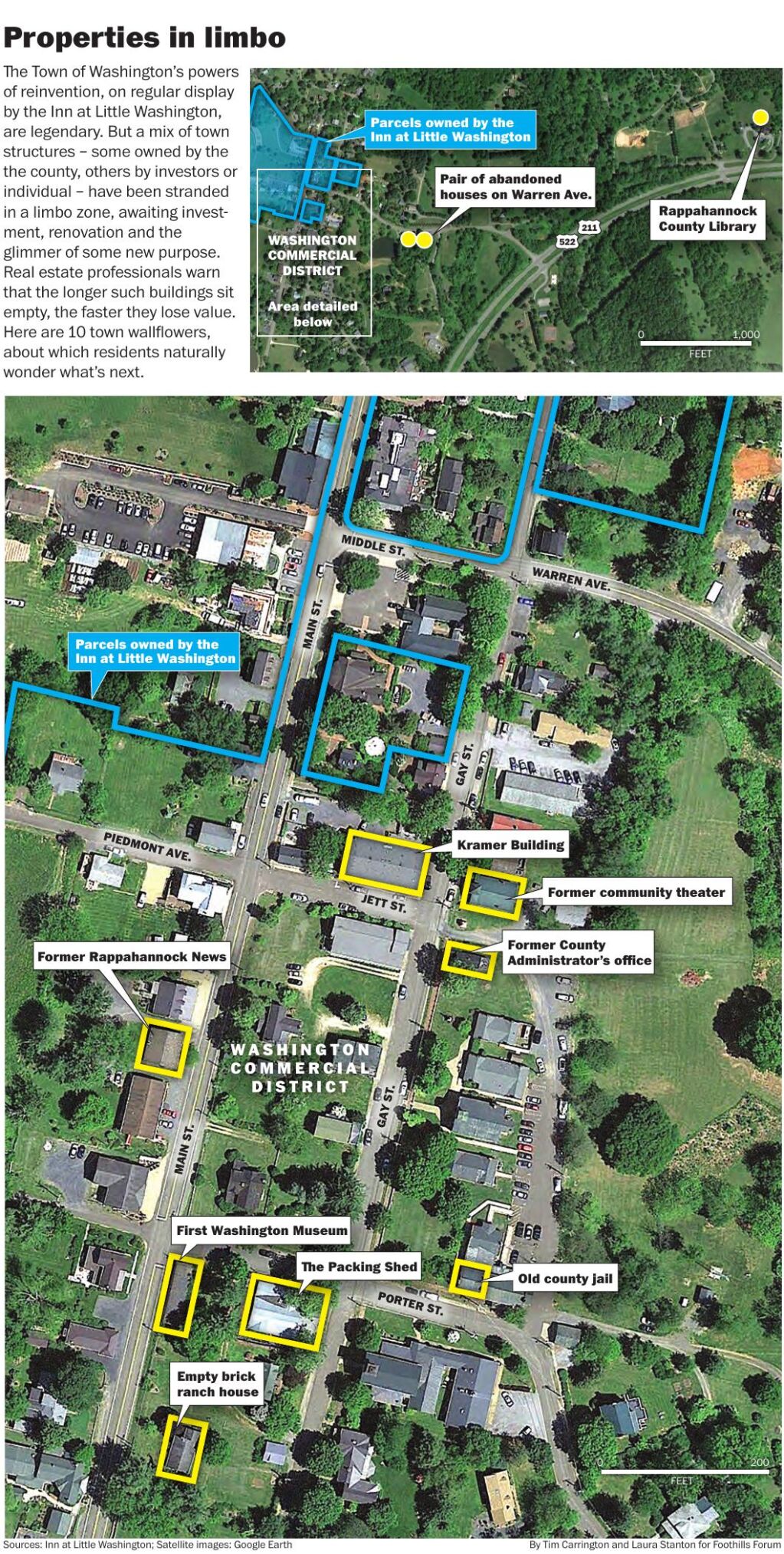

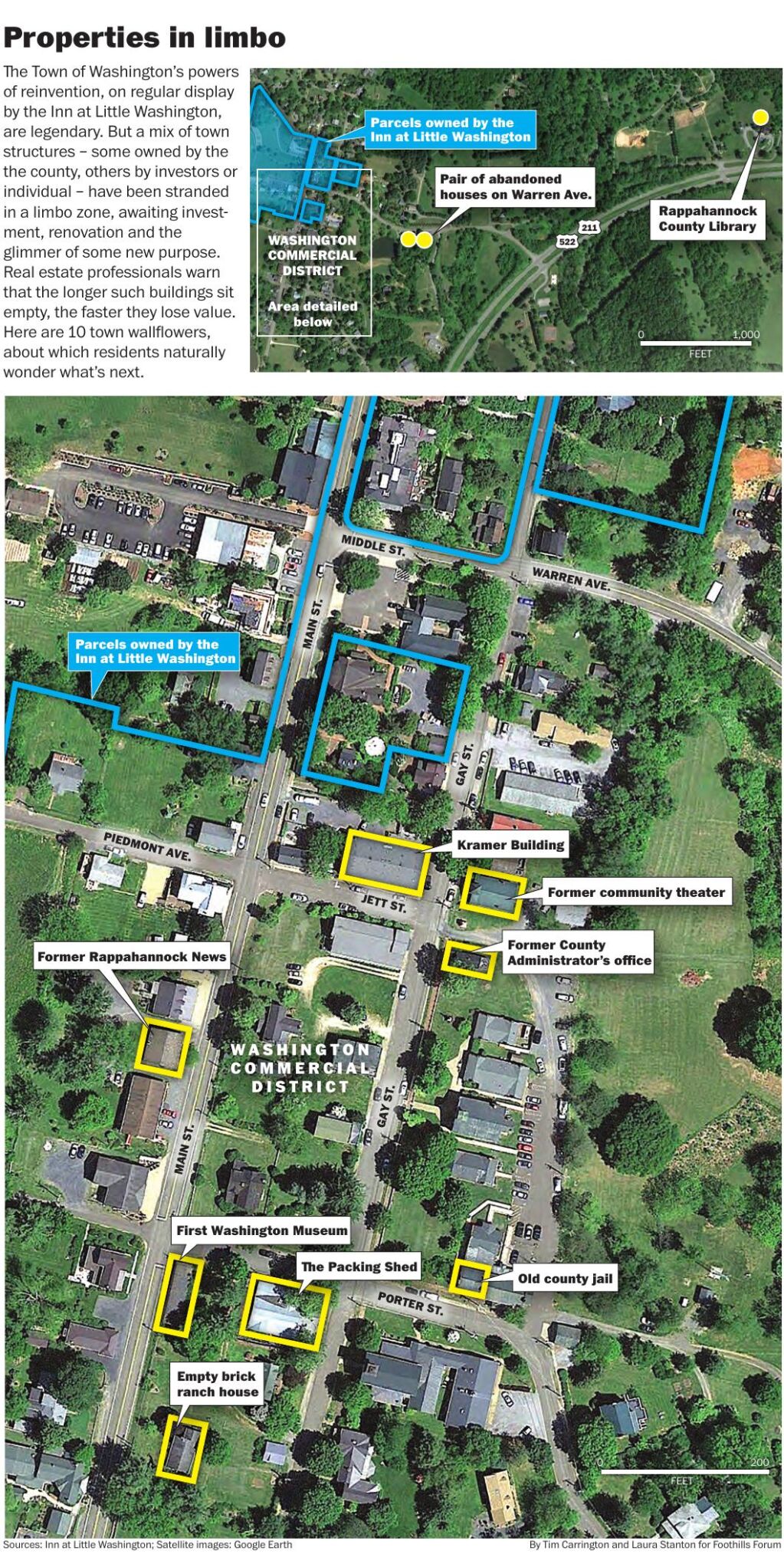

Both patterns are continuing – investment in Washington’s commercial, public and residential structures is estimated to be about $23 million since 2010, with half a dozen major home renovations completed since 2016. But alongside the rejuvenation is a parallel trend: a scattering of residential, public and commercial structures have slid into limbo, waiting for required approvals, bold investors, or an economic environment more supportive of rebuilding and remodeling.

Part renaissance, part limbo

Washington’s peculiar mix — part renaissance, part limbo land — may be unavoidable since different buildings occupy different places in the life cycle. Realtor Alan Zuschlag reasons that the presence of a few derelict or under-used buildings is a small price to pay for a location “that doesn’t become a museum, but a living, breathing town.” The greater worry, he added, would be a push toward “grandiose plans,” artificially imposing a particular pattern on the entire town.

Mayor Joe Whited is concerned about the structures stranded in uncertainty, but he mainly sees continuing renewal. With remote workers joining retired people and weekenders, he says, “We’re on the cusp of something that could be really good.” He predicts that businesses will eventually fill the vacant commercial spaces, and that home renovations will continue. But he added, “We want to maintain the things we love.” His predecessor, Fred Catlin, who continues as a member of the Washington Town Council, underscores the town’s “eclectic” character: In his view, the goal isn’t uniformity of design but harmony within a varied composition.

The former site of the Black Kettle Motel is now the future home to Rush River Commons — which recently cleared the ground for construction. (Photo/Luke Christopher)

Washington’s two biggest projects — Rush River Commons and the Courthouse Row complex — are moving slowly, but in some form, both will come to fruition, albeit after painstaking cycles of scrutiny and approval. The first phase of Rush River Commons, a multi-purpose development project within the current town borders, is underway after three years; but the second phase requires a slight expansion of the town’s boundaries, a controversial change that is subject to continued town-county wrangling. An initial courthouse plan has been sidelined following mainly negative reactions, and alternatives are waiting to gain traction.

Caroline Anstey, who chairs Washington’s Planning Commission, said,“When I first came in 2013, there was a little bit of a sense that things were frozen. Now I see a Renaissance town, a town that’s good at a number of things — food, art, music and drama — and it’s about diversity.”

Unrenewed and unfinished

(Courtesy/Photo)

But while the big projects are inching toward resolution, the un-renewed, unfinished and in some cases un-cared-for corners of Washington will continue to exert political and administrative demands on the town and its residents, as well as on the county, which owns a number of the buildings now stranded in limbo. Washington Treasurer Gail Swift said she worries that Town Clerk Barbara Batson and others involved in clearances, zoning procedures and legal details “will be so busy they can’t see straight” as the various building dilemmas are sorted out.

Here are 10 structures — owned by the county, private individuals or businesses — where the future is unclear. Many enjoyed a storied past, or at least a steady stream of tenants, along with a kaleidoscope of functions reflecting the diverse interests in the county. But the future seems to elude these buildings, each of which is awaiting a compelling idea and a convinced investor. All might plant a sign in front posing the question: “Now what?”

The old Community Theatre building (Photo/Luke Christopher)

The county jail: The historic lock-uphas been without prisoners since 2014, replaced by the regional facility north of Front Royal. Completed in 1836, the building now houses equipment and surplus furniture, and is awaiting a new idea and a new function.

The community theater: Erected in 1890, and now a county property, the space is also in line for a new vision, following earlier lives as a Methodist church, the Washington Town Hall, the Washington Fire Department, Ladies Auxiliary Thrift Store, the Ki Theatre and the Rappahannock Association for the Arts and Community (RAAC) Community Theatre. Expenditures to bring the structure up to code as a theater are exorbitant, and RAAC is now using the larger, newer theater across the street. After staging locally acclaimed productions including “Uncle Vanya”and “Waiting for Godot,” and multiple renditions of “No Ordinary Person,” the older building’s next act will be less dramatic: In its first meeting of the new year, the Board of Supervisors agreed to restore the building for use as “a flexible office space” for county employees while a new courthouse is under construction. Once the new courthouse structure is in place, the county employees will presumably vacate the former theater, setting the stage for another re-think.

The county library: The beloved structuremight expand and renovate at its current location on U.S. Route 211, though the topography of its site presents complications. Or it might move to Rush River Commons in the town center, though opponents of this idea threaten a fight. If the books move elsewhere, decision-makers would face the new dilemma of finding a new purpose for the existing structure.

The Packing Shed with the County Courthouse in the background. (Photo/Luke Christopher)

The Packing Shed: Deteriorating at the corner of Porter and Gay streets, the structure is owned by Jeff Akseizer, an associate of resident investor-developer Jim Abdo. Built in the 1920s as an apple packing facility, it has since been used as a business office, a shop for furniture-maker Peter Kramer, a showroom for antiques, a photography gallery, an office for RAAC, a home for the Washington Thrift store, a studio for painter Kevin Adams, a gallery for the “Six Pack” artists’ group, and a video rental called Cinema Paradiso. The parade of shifting identities may be approaching its conclusion as the building slides into terminal neglect. After a pipe sprung a leak last year, forcing a temporary shutdown of town water, officials have informally raised the idea of razing the Packing Shed.

Empty brick ranch house: Downhill from the Packing Shed and facing Main Street stands an unassuming brick ranch house that has been maintained, but sits empty.

First Washington Museum: The structure at the corner of Porter and Main streets, owned by Abdo, is awaiting a new life. Abdo, whose ambitious 2014 rejuvenation plans ignited one of the county’s least civil debates, owns the structure along with several others in town. He has lowered his local profile to the point of invisibility, offering only vague suggestions of how he might bring the building back to life.

The former County Administrator building with the old Community Theatre in the background. (Photo/Luke Christopher)

The tiny office building on Gay Street: Built in 1857 to serve as a law office, the free-standing, wood-framed work cubicle has been used by Commonwealth Attorneys, private lawyers, the County Extension Office, the Home Demonstration Agent’s office, and the County Administrator. It’s no one’s office now, and sits jammed with boxes and papers.

The Kramer Building (Photo/Luke Christopher)

Kramer building: The building housed Tula’s, the popular eatery and bar, and is owned by Rob and Christine Bangert Grey, who own Whippoorwill Farm on Piedmont Avenue. The Greys have refurbished the lobby and upstairs of 311 Gay St., where Tula’s was located, but haven’t revealed plans for the restaurant itself.

Warren Avenue pair of vacant houses: Visitors approaching Washington from the eastern Warren Street entrance see the newly constructed and landscaped post office along with a pair of empty and dilapidated private houses. Catlin says the structures are “in desperate need of restoration,” but no one expects a solution any time soon.

The former Rappahannock News building on Main Street: Also owned by Jim Abdo, the town has only a preliminary site plan for this commercially-zoned building, but its next use isn’t known.

The Covid lockdown and its impacts contributed to a number of buildings being stuck in limbo. Zuschlag points to a menu of problems inhibiting developers and investors: waves of workers leaving the workforce, building materials snarled up in supply-chain tangles, and rising interest rates in the face of pervasive inflation. “Right now isn’t the time to start big projects or ambitious projects,” he concluded.

However, on the residential side, Covid has actually propelled investments. Three years ago, David Pennington, now a psychotherapist, and Seth Turner, a real estate broker, set out from Washington, D.C., to explore a possible weekend retreat in Rappahannock County, where they had a few friends. They landed on a vacant — and significantly compromised — house at 41 Harris Hollow Rd., with an intact guest house in the back. Covid hit, and the two — both in their 30s — decided to live mainly in Rappahannock County and invest in rejuvenating the entire property they’d bought. “There are nice people, good art, good food and good drink,” said Pennington.

The main house on their Washington property had water in the living room, more water in the basement, a roof needing replacement, a ruined electrical system and a long-cold heating apparatus. The community ties and congenial ambience kept the rehabilitation from becoming a nightmare for its new owners, whose affection for their new home only increased. When Pennington and Turner planned their marriage in October 2022, they opted to hold the ceremony at Washington’s Trinity Episcopal Church, where Turner is now a regular reader.

The experience demonstrates the town’s appeal to young remote workers, who, in this case, faced the ruinous condition of a long-vacant structure. But business investments, or the renovation of county-owned buildings like the jail or the old theater, aren’t as simple as residential makeovers like the one that transformed 41 Harris Hollow Rd.. There, the rehabilitation was the result of two people seeking an address in a location they hoped to inhabit. In contrast, a new business or arts center needs to capture the public imagination, then draw in customers by offering experiences people have reason to value. An owner’s excitement isn’t enough to assure success.

Alexander Neill-Dore, who manages a tightly scheduled home-building and renovation business, is waiting for the commercial activity to catch up with the rehabilitated homes. “For a town with such allure for so many people, it’s odd that there are so many places that are vacant,” he said, adding that as a county resident himself, he’d enjoy another restaurant and coffee shop that he and his girlfriend might frequent on evenings and weekends.

Washington’s various boosters recognize that despite the retirees and remote workers, the town’s population has dropped to just over 100 from a high of 300 in 1900 — a shift duly noted by potential business owners. A more encouraging sign is the local workforce of some 250 people employed by the county’s administrative offices along with the Inn and other businesses in the hospitality sector. Few could afford to live in the town, but if there were more diversions and eateries, they might spend more time and money there. This, at least, will be the case that Mayor Whited says he will make as he meets in coming months with the existing and prospective business community of Washington.