While the focus has been on COVID-19, drug overdose deaths in the state spike to record levels

Addiction, it’s said, thrives in privacy.

So as everything began to shut down in March 2020, and isolation became a way of life during the pandemic, people in the treatment world saw trouble ahead. Recovery in normal times is hard enough. Recovery alone is rife with peril.

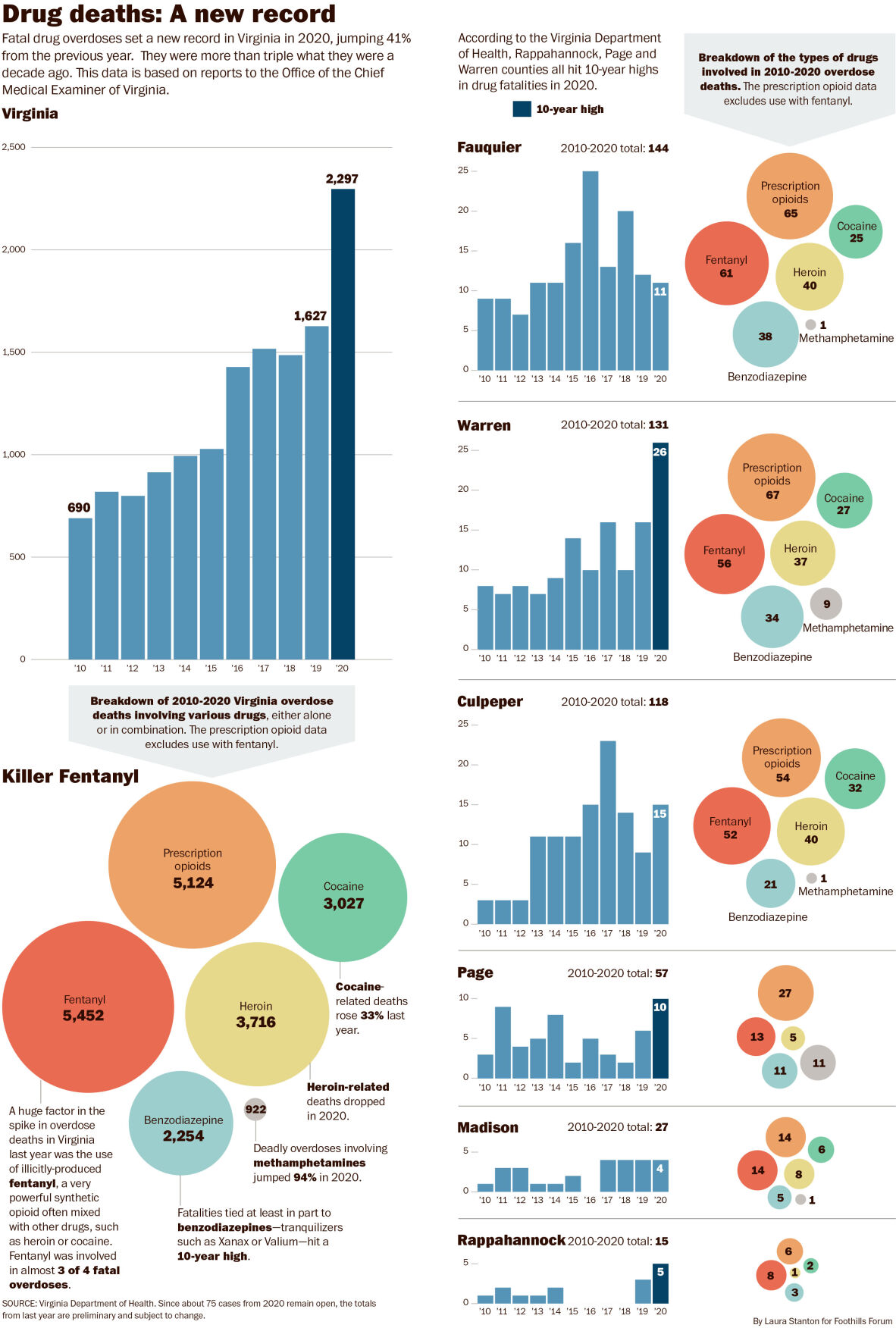

They were right to be apprehensive. According to the Virginia Department of Health, more people died of drug overdoses in the state during 2020 than in any previous year, a total of 2,297. That’s a 41% increase from 2019, which had already set a record.

“The pandemic has had a devastating impact,” said Jan Brown, executive director of SpiritWorks Foundation Center for the Soul, which operates a recovery center in Warrenton. “We’ve seen more people relapsing. We’ve seen more deaths because of the isolation. People are using alone. Help can’t get to them in time.”

Whatever progress had been made in what had been seen as one of the country’s top public health crises — the opioid addiction epidemic — has been eroded by the more pervasive threat of COVID-19. At the same time, those struggling with alcoholism have largely lost access to the in-person peer connections — Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, for example — that help sustain their efforts to stay sober.

“You have the normal stressors, then you add the stress of COVID, then you throw in the social isolation,” said Cory Will, peer recovery program manager for Rappahannock-Rapidan Community Services (RRCS). “A lot of people in recovery rely on a network of other people in recovery. And some people just don’t connect as well virtually.

“Ordinarily, they would be able to go to a meeting and talk through something that’s going on in their lives. They might say. ‘Has anyone had these issues? How have you been managing it?’ You take that piece away, and people are falling off the wagon.”

Sliding into crisis

It wasn’t too long into the pandemic before Dee Fleming started getting calls and emails from anxious parents. This was another ripple of COVID, tied to adult children moving back home after they lost their jobs. Many were using drugs or alcohol, and their parents worried that they were sliding into a crisis.

“We have people just starting their addiction journey because of COVID.” — Dee Fleming, Culpeper parent and advocate, pictured above with her son Joe, who died from a drug overdose. (Courtesy/Photo)

“They were functioning, but the situation was no longer manageable,” said Fleming, whose website, Culpeper Overdose Awareness, is a source of information about recovery programs in the region. She created it after her son, Joe, died of an overdose of cocaine laced with fentanyl in 2017.

She knows that many parents feel overwhelmed and ill-informed when they start looking for help. “It can be extremely challenging,” Fleming said. “I recommend that people first seek out a support group. Parents need somebody to talk to and walk alongside them.”

Unfortunately, the same pandemic that was fueling more destructive drinking and drug use was restricting the services that treat those disorders. The Boxwood Recovery Center, a 28-day residential treatment program in Culpeper, had to halve its capacity to meet social-distancing restrictions. No in-person visits were permitted, meaning any support from family or friends had to come through a video screen. Plus, the center closed its detox program to use that space as a quarantine area.

The basic logistics of getting help have become more complicated, too. Instead of being able to just show up at the Warrenton or Culpeper outpatient clinics to be evaluated for mental health or substance use issues, people now must make an appointment a day in advance. And, while there’s more flexibility these days, initially most counseling was done virtually, a challenge for both therapist and person seeking help, particularly if he or she didn’t have access to a reliable broadband connection.

When support groups did start up again, they, too, usually met online. That made it harder for some people to engage, particularly those who were new to a group. And clicking on a Zoom link required considerably less commitment than getting dressed and heading out to a meeting. “I’ve seen meetings where somebody’s just lying in bed,” said Will, the RRCS peer coordinator. “Are they really trying to take the next step forward?”

Renee Norden, executive director of the Mental Health Association of Fauquier County, suspects that the true impact of the pandemic on substance use is only now becoming apparent.

“As we’re able to see more people in person, we’re going to find more people worried about friends and loved ones,” she said. “For example, people can be in denial about how much they’re drinking. It’s not until they get around other people who see they’re drinking three beers for every one everyone else is drinking.”

Responding to COVID

Last July, as drug overdoses kept climbing, a new state law went into effect. It prevents police from arresting for drug possession anyone who seeks help for a person experiencing an overdose, as well as those who administer care on-scene. Supporters of the legislation say it will save lives because it keeps people from hesitating before contacting authorities.

(Graphic/Laura Stanton)

But Fauquier County Sheriff Robert Mosier contends that there also have been less positive effects: Officers are being called to the same house multiple times and are not able to take any legal action. That’s frustrating to them, he said, and it means a person with a drug use disorder is less likely to get treatment.

Working with RRCS, Mosier’s department has been overseeing a program at Fauquier’s adult detention center where inmates can receive both counseling and access to Vivitrol, a drug that helps prevent relapses by blocking the effects of opioids. Research has found that former inmates are far more likely to die of a drug overdose within the first two weeks of their release from jail.

“Not everyone has the money to go to an expensive rehab program,” he said.

At the federal level, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, in response to COVID, has relaxed its regulations on people receiving methadone as part of medication-assisted treatment. Instead of being required to go to a clinic every day, patients receive 28-day take-home supplies. The Drug Enforcement Agency began allowing certified physicians to prescribe buprenorphine, a drug that reduces addiction cravings, without seeing a patient in person. A telephone evaluation will suffice.

Just last month, federal health officials went a step further, announcing that doctors, physician assistants and nurse practitioners will be able to prescribe buprenorphine without going through a special training program. The goal is to make the treatment more accessible in rural communities, where doctors are in short supply.

While he supports making buprenorphine available to more people in need, Dr. Ash Diwan, a physician at Piedmont Family Practice who is certified in addiction medicine, is concerned that with so many health professionals permitted to prescribe the medication, other aspects of treatment will get short shrift.

“It has to be about more than dispensing medicine,” he said. “There has to be a counseling component. If it was just like writing a prescription for an antibiotic, it would be easy. But it’s not. That would be treating a chronic problem like an acute one.”

Lost momentum

That’s a common concern in the treatment community, that the push to better educate the public about the chronic nature of addiction has lost momentum in the pandemic, that reducing the stigma of substance use as a moral failing rather than a medical condition has faded.

There have been some gains. More patients have eventually gravitated to virtual support groups, not only eliminating transportation issues, but also enabling them to meet peers all over the world. Thanks to telehealth, more people are making their therapy appointments.

“You hear about alcohol sales going through the roof. When is that going to start showing up?” — Cory Will, far right, peer recovery program manager for Rappahannock-Rapidan Community Services with his team (Photo/Coy Ferrell/Fauquier Times)

Cory Will said he is encouraged to see that people with substance use disorders are more likely to view their condition as a mental health issue.

“I sat in on an AA meeting, and there were a dozen people there,” he said. “Not one person brought up drinking. They talked about mental health, about feeling alone and being anxious.”

But the illicit version of the powerful painkiller fentanyl continues to be a deadly wild card, playing a role in almost three out of four overdose deaths in Virginia last year. And deaths related to methamphetamine rose precipitously in the state in 2020.

Will is worried about the long-term costs of such a prolonged period of stressful isolation. “You hear about alcohol sales going through the roof,” he said. “When is that going to start showing up?”

Dee Fleming has the same concern.

“We have people just starting their addiction journey because of COVID. We’ve had people who’ve been in recovery five years pick it back up again. People are using more alone than they used to,” she said.

“I really think that if we don’t start getting a handle on the substance use issue again, five years from now we’ll be asking, ‘How did it get this bad?’”

What family and friends should know

There was a time when the conventional wisdom said that a person could not begin to address his or her substance use issues until they hit “rock bottom.” It’s a term you never hear in the treatment community any more. As Renee Norden, executive director of the Mental Health Association of Fauquier County, put it: “If somebody had all the symptoms of diabetes, would you say we’re going to hold off until they go into diabetic shock before we do anything?”

Here are other fundamentals of substance-use recovery.

-

Addiction isn’t a matter of choice. It’s a treatable, chronic disease.

-

Detoxification is only the first step of treatment and is rarely sufficient on its own to lead to long-term recovery.

-

It is very difficult for opioid drug users to quit by themselves. Relapse is common.

-

Many people with substance-use issues also have mental health disorders, which can make recovery even more challenging.

-

Boredom and isolation are top reasons for relapse early in the recovery process.

-

It’s important for people in recovery not to have temptations or triggers in their homes.

-

Long-term drug use can cause profound changes in brain structure and function that result in uncontrollable drug craving.

-

Treatment that addresses many aspects of a person’s life — including mental and physical health — can be most effective at helping end or reduce using.

-

Treatment can include counseling, medication and behavioral therapies, which can also be used in combination.

-

Dwelling on the past is counterproductive for someone in recovery.

Sources: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the national Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Voices

Fighting alcoholism in the time of COVID

Taylor, 30, works in the home improvement business in Culpeper. He started drinking when he was 15. Now, he says, it’s a “problem.” He asked not to be identified due to the stigma tied to his substance-use disorder. Here’s his take on what it has been like to deal with his drinking during the pandemic.

When did you start to think you might have a problem?

Probably within the past two years.

Why?

In August 2019, I got my first DUI. That was kind of a red flag. That December, I went into a 30-day program. Then COVID hit a couple months later. With COVID, it was just hard. There were no AA meetings, and for me, in-person meetings are better.

When did you start going to Alcoholics Anonymous?

I had actually been going to AA meetings and Restore Culpeper meetings before my treatment and even prior to my DUI arrest. I was trying to figure out if I did have a problem or didn’t have a problem. I don’t know that I so much have a problem with alcohol. I have some mental health issues from loss of family members. and worrying more about other people and not myself. That built up on me over the years, and alcohol was my solution.

Was being in a peer group beneficial?

Yes and no. It was beneficial if I listened. You can do anything or go anywhere for treatment, but until you decide for yourself that it’s time to get your act together, you’re not going to.

What was your reaction when COVID started?

It was kind of an “Oh crap” moment. I have to do this on my own. With the sober network, it’s kind of like a family. I stayed in contact with people via phone. But it felt like you were suddenly on an island.

What did you miss most about it?

Well, Monday nights I was doing the Restore meetings.* And pre-COVID, I was doing at least two AA meetings a week. When you go to those meetings, it’s like being part of a team. We’re all trying to win the game of staying sober. I think mainly I missed the fellowship of being around people like me. I stayed plugged in with my community, but when COVID hit, it was more on-again, off-again, on-again, off-again.

Did you start to drink again once the COVID lockdown began?

Not right away. I made it to about the middle of summer. Then the wheels started to wobble. We had had our first child in January, and there was a lot of stress from that. You know, becoming a parent amidst all this COVIDness.

So, how did the drinking start again?

I was a closet drinker so no one knew. I’d drink coffee to mask it. And you get into the mindset of “Well, I don’t know when I’ll be able to do this again, so I’ll drink as much as I can.” When I did, it got messy quick.

What’s been happening since then?

In March, I got my second DUI. I’ve been sober since then.

How has your drinking affected your relationship with your wife?

When I got arrested the second time, I thought that was going to be it for my marriage. We’ve been married less than two years.

But my wife is phenomenal. She sees the potential in me. But I do think this is it for me if I screw up this shot. It’s more motivation to stay on track. I’m out of jail on bond [for the second DUI], and if I’m out drinking and get caught by law enforcement, I’m going to jail for a long time.

Are you feeling hopeful?

I’m starting a new outpatient treatment program three nights a week. It’s therapy and group meetings. All virtual. I didn’t want to do it, but I can’t really leave any option on the table now.

What do most people not understand about recovery?

It’s not that we’re bad people. As part of our addiction, we can make bad decisions. It’s really hard to get people to understand that. Also, anyone can go away for 30 days or 90 days, but if you don’t learn how to live your normal life sober, it’s not going to work.

Do you think there will be long-term consequences of the pandemic for people in recovery?

Absolutely. Our overdose death rates have been up. That’s as long-term as it gets.

* Restore Culpeper is a 12-step support group started by the Mountain View Community Church.

Where to get help

Helplines

24/7 Crisis Hotline: Deals with mental health, health and substance use situations. 540-825-5656.

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255.

NeverUseAlone: 24/7 peer-run call line. 1-800-484-3731.

Peer2Peer Regional Warmline: Not a crisis line, but callers connect with peers with experience in mental health and substance use issues. 833-626-1490.

Therapy and recovery services

Boxwood Recovery Center: 28-day residential substance use recovery center in Culpeper that provides individual, family and group counseling. 540-547-2760. https://www.rrcsb.org/boxwood-recovery-center/

Herren Wellness at Twin Oaks: Holistic residential addiction recovery center in Warrenton. 844-443-7736. [email protected]

Rappahannock-Rapidan Community Services: Agency that provides outpatient mental health and substance use counseling and clinical assessments to determine treatment needed. Warrenton clinic: 540-347-7620. Culpeper clinic: 540-825-3100. 24/7 Crisis hotline: 540-825-5656. https://www.rrcsb.org/

SpiritWorks Foundation Center for the Soul: Peer-to-peer addiction recovery support. Warrenton office: 540-428-5415. https://www.spiritworksfoundation.org/

Resources and family support

Al-Anon: Online meetings for those affected by the alcoholism of others. https://al-anon.org/al-anon-meetings/electronic-meetings/

Center for Motivation and Change: A guide for parents and partners to people with substance use disorders. https://the20minuteguide.com/

Come As You Are Coalition (CAYA): Fauquier nonprofit that maintains online listing of resources, treatment options and support groups. https://www.cayacoalition.org/

Culpeper Overdose Awareness: Comprehensive online resource of treatment options, recovery meetings and support groups in the region. https://www.culpeperoverdoseawareness.org/

Families Anonymous: 12-step program for relatives and friends of people with drug or alcohol issues. https://www.familiesanonymous.org/

Mental Health Association of Fauquier County: Nonprofit that provides information and guidance on mental health and addiction resources and treatment for Fauquier and Rappahannock residents. 540-341-8732. https://www.fauquier-mha.org/

Nar-Anon: Support chat rooms for those affected by another’s addiction. https://www.naranonchat.com/

ParentsHelpingParents: Virtual meetings for parents of children with substance use disorders. https://www.parentshelpingparents.info/virtual-chapter

Partnership to End Addiction:Website for parents seeking help for their children. https://drugfree.org/

SMART Recovery Family and Friends: Secular, behavioral-based program that offers online meetings for families and friends of those with substance use disorder. https://www.smartrecovery.org/family/

Peer support groups

Regional meetings: https://www.culpeperoverdoseawareness.org/meetings/

Alcoholics Anonymous virtual meetings: https://aa-intergroup.org/

Narcotics Anonymous virtual meetings:https://virtual-na.org/meetings/