For decades, Rappahannock has been able to preserve its natural beauty and stunning views. But more challenges are on the horizon.

A RAPPAHANNOCK NEWS-FOOTHILLS FORUM SPECIAL REPORT

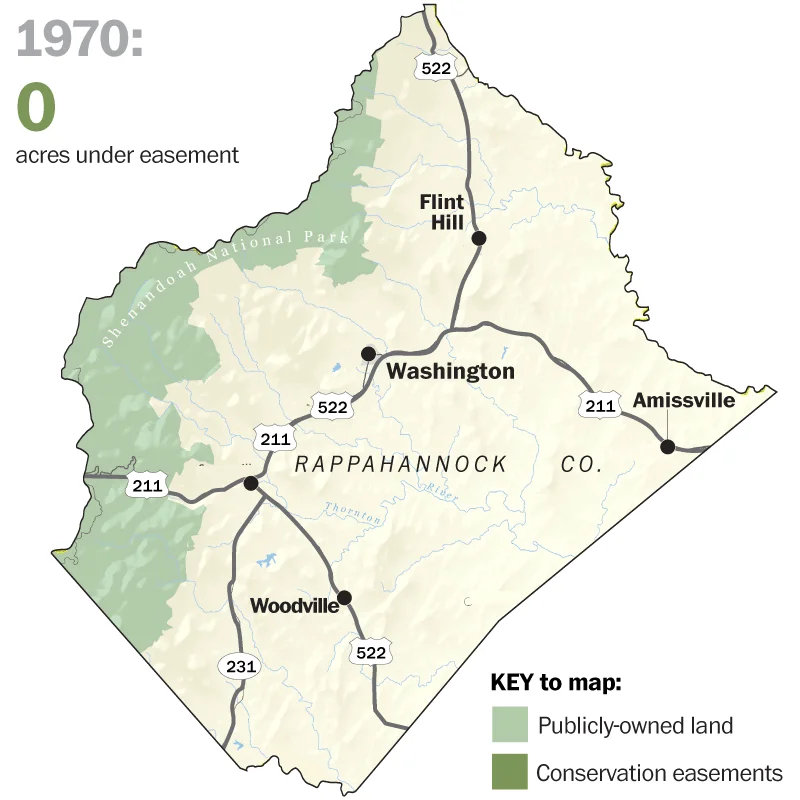

File Image/Oct. 2020: Conservation easement growth: Roughly 24 percent of the land in the county outside Shenandoah National Park is now protected through conservation easements. (Graphic/Laura Stanton)

Soon, Rappahannock’s Board of Supervisors is expected to approve an updated version of the county’s Comprehensive Plan. It’s a hefty document, almost 120 pages long, dappled with maps, graphs and stacks of data.

Then there’s Chapter Six. That’s where statistics and fact-filled sections give way to aspirations; specifically, how to hold on to what matters most to Rappahannock residents. They’re refined into a list of concise goals. At the top: “Preserve the overall viewshed of the county in its unspoiled natural setting, which gives it special character and identity.”

That’s followed by three other priorities, all having to do with preservation. One calls for protecting the county’s mountains and “scenic ridgetops;” another, its ground and surface waters; the third, its “rural, agricultural and open spaces.”

For decades, that’s been the heart of Rappahannock’s de facto mission statement, and there’s no indication it will change any time soon. But the challenge of protecting all of the above is intensifying due to an assortment of real and possible threats — from the prospective sale of the 7,000-acre Eldon Farms, to the struggle to keep family farms intact, to the potential for more towers to address inadequate broadband and cell service to the impact of climate change and invasive species.

“The question,” said longtime local environmentalist Phil Irwin, founder of the Rappahannock League for Environmental Protection (RLEP), “is how do you maintain the conservation ethic?”

Hilltops on the horizon

The viewshed comprises many things. But for many, it starts with the hilltops on the horizon. Some old-timers, like cattle rancher Jim Manwaring, will tell you that few changes irk them as much as the houses he now sees there.

“Houses that are built in prominent places that are visible from all around. That just devastates me,” he said. “You go from this beautiful pasture to a little suburb on the mountainside.”

Time was when the county would send a brochure to anyone from outside Rappahannock who bought property here. While it welcomed newcomers to country living, the pamphlet also tried to discourage them from putting up homes on scenic hilltops. It pointed out the not insignificant cost of building on ridges, warned that fire trucks and rescue vehicles might have trouble climbing steep hills, that heavy rains can erode driveways, and that can pollute streams.

The message, while cordial, wasn’t subtle. “Remember, while building on a hill can give you a great view of nature, that vista can easily give way to a view of hillsides covered with houses instead of trees and fields,” it read. In short, it advised, be considerate and “avoid destroying the very things that attracted you to Rappahannock County.”

Scars on the land

New property owners no longer get the brochure. Apparently, it didn’t survive the transition from longtime county administrator John McCarthy in 2016, although an online version still exists deep inside the county’s website.

Some bristled at what they saw as government overreach, McCarthy recalls, but more often the sentiment resonated.

“There’s this sense that people here don’t like houses being built in the viewshed, and that has helped discourage people from building on ridgetops,” said Al Henry, the Hampton District representative on the county’s Planning Commission. “Public opinion has made that kind of a taboo. And people coming out here don’t like to violate environmental taboos.”

Board of Supervisors Vice Chair Chris Parrish, whose Viewtown farm features a striking Blue Ridge panorama, agrees that appealing to the public’s desire to keep the viewshed uncluttered is the best approach. He believes that from an enforcement standpoint, there’s not much more the county can do.

“The only real way we’re going to stop hilltop development is moral suasion,” he said. “You can’t take people’s property rights away.”

But the county’s simple beauty can belie its environmental complexity, and the notion of becoming stewards of the land doesn’t necessarily convey with a rural address.

“We’ve got to do a better job of protecting what we have,” said Theresa Wood, president of Businesses of Rappahannock. She remembers picking up the brochure in a real estate office when she was looking for property. It was one of the things, she said, that sold her on Rappahannock.

She thinks there’s a need for more focus on educating people about the impact they have on their surroundings. “When someone buys land, we need to give them more information. If you want to keep dark skies, here’s who to contact. Or think about how your roof is going to reflect sunlight.

“We could be more proactive in that way because I think most people who move here don’t want to be a scar on the land.”

The preservation tool of choice

”The good thing is I’m always learning. That includes learning about what matters most to people about their land here,” says the Piedmont Environment Council’s Claire Catlett. (Photo/Dennis Brack)

Claire Catlett is all about educating people. She’s the Piedmont Environmental Council’s (PEC) land conservation field representative in Rappahannock County, and in that capacity works with landowners in protecting streams and wildlife habitats on their property.

She also talks with them about conservation easements — voluntary, legal agreements that permanently limit how land can be used or developed. That sometimes involves clearing up confusion about what entering into a preservation partnership with a land trust means. Land trusts are organizations, such as the Virginia Outdoors Foundation (VOF), that take legal ownership or stewardship of a property through a formal arrangement with the landowner.

For instance, it doesn’t restrict you from farming the land, or even erecting buildings on it, although there could be restraints on their size and location.

“If someone has children who might want to build their own house on the property, we make room in the easements for those types of decisions in the future,” Catlett said. “There are constraints, but the landowners are part of that process.”

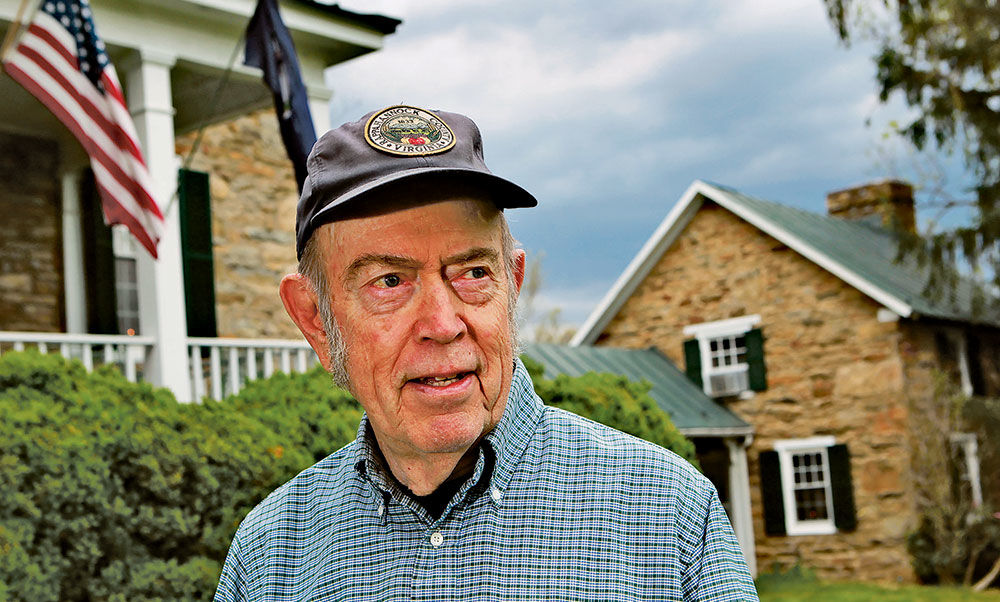

Phil Irwin, who cofounded RLEP, set up the county’s first easement on his farm outside Flint Hill in 1973. (Photo/Dennis Brack)

The fact is Rappahannock is already a state leader in terms of both the number of (VOF) easements on private land — it ranks fourth in Virginia with 221 — and the acreage they cover — fifth, with 31,229 acres. That means roughly 24 percent of the private land in the county outside Shenandoah National Park is protected in perpetuity.

Phil Irwin set up the first easement in Rappahannock on his Caledonia Farm outside Flint Hill in 1973. Sixty-two more were added over the next 26 years. But the big spike came in the first decade of the 21st century, when 135 more were created.

There were several reasons, not the least of which was a generous 50 percent tax credit from the state. That was when then Gov. Tim Kaine, a big easement evangelist, set a goal of 400,000 protected acres in Virginia. So was then county administrator John McCarthy, now the senior advisor and director of strategic partnerships with PEC.

Back then, easements were seen as the preservation tool of choice. “A big group of us did it around the same time,” said local real estate agent Cheri Woodard, who with her husband, Martin, put an easement on their land in 2005. “The feeling was that if you really wanted to protect this county, this is what you should do.”

Another force driving the movement was the Rappahannock County Conservation Alliance (RCCA), a nonprofit that focused on educating landowners about easements and raising money to help farmers cover the costs of entering into a land trust partnership.

Altogether, it contributed a total of $140,000 to the county in conjunction with the state’s Farmland Protection Program. That resulted in three working Amissville farms being placed in easement — the Muskrat Haven Farm, the Meadow Grove Farm and the Levi Atkins Farm.

But interest in that program waned, and the county ended up using money from RCCA for other general budget expenses. In 2014, the RCCA merged with the Krebser Fund, a component of the PEC, which also funds conservation programs in Rappahannock.

An easement slowdown

Since 2010, an additional 53 easements have been created in Rappahannock, a drop of more than 60 percent from the previous decade. It didn’t help that the state’s tax credit was lowered to 40 percent of the value of the land in easement, and also that last year the IRS changed its regulations so that landowners with easements will have to subtract their state tax credit from their federal charitable deductions.

Another factor is that the easements in partnership with VOF — which account for almost 90 percent of the agreements in Rappahannock — became more restrictive, to the point of even prohibiting certain paint colors in viewsheds. It has, in recent years, become more flexible, according to Jason McGarvey, VOF’s communications and outreach manager, particularly in supporting people with working farms and forests. But the micromanaging reputation has lingered.

Finally, when it came to potential easements in Rappahannock, much of the low-hanging fruit had been picked, Most of those enamored of easements for financial and emotional reasons have already made the commitment.

Among those who have resisted putting their property in easement are some big landowners who are wary of the impact that could have on their children and future generations. That includes Bill Fletcher, whose family has farmed in Rappahannock for almost 300 years. He now owns about 1,000 acres. None of it is in easement.

Fletcher said that he likes the idea of easements and the role they can play in protecting the county’s natural beauty. But he thinks it doesn’t make sense for him because he believes it could eliminate or limit some future options for generating income from his land, particularly those that don’t involve farming.

“Easements are forever so you’re taking a helluva risk,” he said. “You could end up losing a lot of value on the property. Having an easement is a short-term advantage and a long-term problem.”

Leslie Grayson, a deputy director at VOF, acknowledged that people need to go into conservation easements with their eyes open, recognizing that while the legal document is fixed, the land itself can change.

“The biggest failing of all is easement remorse,” she said. “If that happens, everybody’s failed. Land conservation is a balancing act, and you need to be aware of that, and not just a blind believer. You want it to endure.”

Eye of the hurricane

For those who want to be stewards of their land, but are skittish about a forever commitment, there are plenty of other options, some for which grants or cost-sharing arrangements are available. They range from creating wildlife habitats or pollinator meadows for bees and butterflies to planting trees along streams to reduce erosion to managing fields and forests in ways that improve soil quality and preserve wooded areas.

The Culpeper Soil and Water Conservation District offers a number of these programs. So do the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Virginia Department of Conservation and the Virginia Department of Forestry.

Part of Claire Catlett’s job at PEC is to connect local landowners to those resources and help them find ways to preserve their slice of Rappahannock. She said it can sometimes feel overwhelming to stay on top of all the factors that can enhance or destroy a natural asset.

“The good thing is that I’m always learning,” she said. “That includes learning what matters most to people about their land here.”

Education is likewise a major focus of RLEP, with its Dark Skies initiative a prime example. Two years ago, it began encouraging local businesses, churches and homeowners to replace their outdoor lighting fixtures with ones that reflected light downward instead of into the night sky. Thanks to a grant from the PATH Foundation, it’s been able to provide free the replacement fixtures, almost 200 in the county so far, according to RLEP board member Torney Van Acker.

Torney Van Acker (Photo/Chris Kagy)

Van Acker said that instead of going to the Board of Supervisors and demanding a change in the county’s lighting ordinance, RLEP chose to promote the environmental and economic benefits of down-shielding lights through Dark Skies programs at local schools and the county park, and through one-on-one conversations.

“People see the benefits because the lights are cheaper to operate, they last longer and the light is directed where they want,” he said. “And the neighbors stop complaining.”

There have been other Dark Sky victories. The Rappahannock Electric Cooperative has agreed to use down-shielding lights when it needs to replace fixtures. And last year, the International Dark Sky Association named Rappahannock County Park a “Silver Tier Dark Sky Park,” one of only three in Virginia.

“Rappahannock County is pretty much the only place around which has a chance of having a sky that’s reasonably dark,” Van Acker said. “The message we like to convey is that it’s like the eye of the hurricane.”

Lessons to be learned

“Rappahannock County is pretty much the only place around which has a chance of having a sky that’s reasonably dark,” said RLEP board member Torney Van Acker. Above, a view of Sperryville from Skyline Drive. (Photo/Dennis Brack)

That message extends beyond the night sky to all the other elements that make Rappahannock’s viewshed so unique. But local environmentalists see trends that are making them realize they will need to step up their efforts to educate landowners about the ways to preserve what’s here — whether it’s through creating conservation easements or simply protecting the wildlife that passes through their property.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made land in the country that much more appealing to city dwellers. Also, there’s a sense that in the coming years, more parcels of land will become available as more farmers put pieces of their properties on the market to stay afloat.

And that could bring a wave of newcomers to the county who love the views, but know little about how to maintain them.

For people like Van Acker, it’s just another aspect of keeping conservation front of mind in a place that has the most to lose.

“One of the challenges is sustaining environmental action in the county,” he said. “Lots of people want to do the right thing, but the pressures of everyday life occupy them.

“And they end up taking a more convenient path.”

The Series

Part 1 (Oct. 29) For decades, Rappahannock has been able to preserve its natural beauty and stunning views. But more challenges are on the horizon.

Part 2 (Nov. 11): Preserving a rural landscape is closely linked to maintaining a robust rural economy. Land-use tax breaks, innovations in product lines, distribution and marketing all help, but farms are still getting smaller, and fewer.

Part 3 (Nov. 26): The views get most of the attention, but the county’s water and soil quality are a critical part of its environmental health. What shape are they in?

Part 4 (Dec. 9): It may appear to be frozen in time, but Rappahannock is always in a state of flux. How it deals with such challenges as climate change and invasive species may be a key to its future.

This series is funded in part by a grant from the Rappahannock League for Environmental Protection (RLEP). In compliance with Foothills Forum’s Gift Acceptance Guidelines, RLEP had no role in the selection, preparation or pre-publication review of these stories. Foothills Forum is an independent, nonpartisan civic news organization whose mission includes providing in-depth explanatory reporting on issues of importance to Rappahannock County.